By Caroline Porter

Dec. 9, 2019

Co-published by the Institute for Nonprofit News and the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. PDF version can be downloaded here.

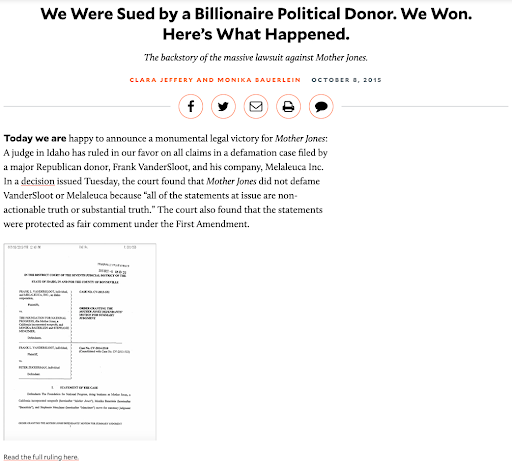

In February 2012, the nonprofit news organization Mother Jones published a seemingly ordinary story that would prove to change its fate. The story profiled a Republican donor, Frank VanderSloot, and among other things, his treatment of a gay journalist. Shortly thereafter, VanderSloot and his company, Melaleuca Inc., filed a defamation lawsuit against Mother Jones, beginning a nearly three-year saga that ended in 2015 with a judge in Idaho ruling in the magazine’s favor. “All of the statements at issue are non-actionable truth or substantial truth,” the judge found, protected as fair comment under the First Amendment.

Throughout the ordeal, the leaders at Mother Jones made two choices that illustrated strategic decisions. They were decisions that would make a striking difference for Mother Jones’ future as not only one of the oldest nonprofit news outlets but also one of the most successful.

First, they opted to fight the lawsuit rather than settle it. The leaders at Mother Jones saw the lawsuit as an effort by VanderSloot to use the courts to quash factual reporting that he did not like, leveraging his fortune to intimidate journalists and rewrite history to his liking. “It was a difficult decision [to fight the lawsuit]. Pay $74,000, and [provide] the admission that we were wrong — that’s all we had to do,” said Monika Bauerlein, now Chief Executive Officer of Mother Jones. “We were really grounded in the mission of fearless journalism, and without that, why are we doing it?”

The second critical decision came after the judge’s ruling, when Bauerlein and now Editor-in-Chief Clara Jeffery published a 2,700-word tell-all about the experience, “We Were Sued by a Billionaire Political Donor. We Won. Here’s What Happened.” Using the column as a launching pad for a fundraising campaign, the news organization raised $350,000 of the $850,000 spent to fight the lawsuit.

The experience became a pivotal moment for Mother Jones, clarifying its purpose and pitch to staff and readers alike.

At a time when many publications responded to economic pressure by shifting to lighter, less-expensive reporting, the decision to fight the lawsuit reflected a decision by the leaders of Mother Jones to intensify their investigative news focus.

The decision to talk frankly with readers about the legal attack, its cost and its effect on the overall organization and its reporting — that veered from journalism tradition. The inside workings of news organizations traditionally have been kept just that — inside. Mother Jones, frank and forthright in its editorial tone, opted to extend its reporting approach and its voice throughout its business operations, to voice its journalism mission and to cover it like a story, for its readers and the world. These moves and others at Mother Jones now are studied by many in the industry, because this 43-year-old publication is growing, fast. And that poses a riddle that fascinates and gives hope to those watching the rapid decline of most other media.

How did Mother Jones grow its audience, revenue and reporting staff in a period when most news magazines downsized, and many closed altogether?

Founded in 1976, Mother Jones is the nation’s oldest investigative nonprofit news organization, and boasts the largest audience (on its own platform) among such organizations. From its beginning, the magazine put as much emphasis on audience development and functional business operation as it did on editorial. Within a year of launch, for instance, thanks to a professional direct mail program that helped the publication stand out from its competitors, Mother Jones’ circulation had grown to more than 200,000 subscribers. That legacy created a foundation for the pivot to a multiplatform approach and a deeper relationship with digital readers that transformed the organization in the past decade.

While historical heavyweights like Newsweek pivoted to become digital-only publications, others shuttered completely, such as The Weekly Standard, Pacific Standard, and The Village Voice. Print consumer magazine advertising revenue in the U.S. has dropped from $12.7 billion in 2014 to $9.7 billion in 2018, according to PwC LLP’s Global Entertainment & Media Outlook: 2019-2023. Circulation revenue from U.S. print consumer magazines also declined in recent years, from $7.2 billion in 2014 to $6.5 billion in 2018.

Across the industry, one in four newsroom positions disappeared between 2008 and 2018, according to a July 2019 Pew Research Center report, as the total number of newsroom employees in the U.S. plummeted from 114,000 to 86,000.

By contrast, the number of people getting news from Mother Jones grew by 17 percent from 2014 to 2019, to a total audience size of 8 million unique visitors a month, including social followers across platforms, web traffic, print subscribers and podcast listens. The online and print magazine’s budget increased in recent years, which in turn has allowed for an uptick in hiring and reporting. Between 2014-2015 and 2019-2020, MoJo’s budget increased from $13.5 million to $18.1 million, and MoJo’s staff increased from 73 to 93 staffers. In 2017, the news outlet was named the Magazine of the Year in 2017 by the American Society of Magazine Editors, and in 2019, Bauerlein and Jeffery were awarded the I.F. Stone Medal for Journalistic Independence.

The magazine was less dependent on advertising revenue than many of its peers, which were hit hard by the decline in ad rates across print and digital. By the end of 2019, it expects to raise $25 million through its “The Moment for Mother Jones” fundraising campaign, a striking achievement for the field of journalism.

Mother Jones’ success diverges dramatically from the fortunes of most news publications in the last five years. What made the difference? Among many factors — culture, leadership, great journalism — four threads offer patterns that other publications can borrow from in finding new paths for news.

First, the news organization doubled down on its commitment to investigative journalism, applying this priority as its north star in decisions big and small. Second, leaders took a “reader focus” strategy and deepened and spread it across both business and editorial sides of Mother Jones. Third, the online and print publication leveraged disciplined fundraising methods that had been successful in the broader nonprofit sphere, namely campaigns, to structure and grow its message. Fourth, MoJo made a habit of “small bets” to experiment with constantly evolving opportunities in media.

Mother Jones published its first print magazine in 1976. The progressive, nonprofit news organization took its name from Mary Harris Jones, an activist who fought for the working class at the turn of the 20th century and used the nickname Mother Jones. With a focus on investigative journalism, the magazine earned a loyal base of magazine subscribers and success for its muckraking exposés. Today, its mission is “to deliver hard-hitting reporting that inspires change and combats ‘alternative facts.’” Mother Jones describes itself as a reader-supported investigative news organization that “goes deep on the biggest stories of the moment, from politics and criminal and racial justice to education, climate change and food/agriculture.”

About 17 years after Mother Jones’ entrée in print, an interest in new ways to reach readers led MoJo to become the first “nongeek” magazine to place itself on the world wide web in 1993. By 2006, leaders at the magazine saw that its core of print subscribers was aging, while the web was becoming a mainstream technology for a growing base of readers. At the same time, Bauerlein and Jeffery became co-editors-in-chief of the magazine.

Together they collapsed separate digital and print editorial teams into one team and transformed the enterprise-story magazine into a two-pronged news organization that produced daily news coverage as well as long-form feature writing.

To implement these choices, Bauerlein and Jeffery pivoted from relying on freelancers to hiring full-time reporters and establishing MoJo’s first bureau in Washington, DC. They saw this as a necessary move in response to readers’ needs for deeper investigative reporting following the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

“Number one, we knew we needed more coverage out of D.C.,” said Jeffery. “We had a window into coverage we could do better.” She said that oftentimes freelancers couldn’t go down rabbit holes because they couldn’t afford to follow up on stories, restricting the kind of investigative reporting that Mother Jones prided itself in.

Within six years, the investment in full-time reporters was paying off. MoJo made waves on the national media scene with investigative scoops, most notably with the “47 percent” story in September 2012. Mother Jones’ Washington, DC Bureau Chief David Corn published a secret video of then-Presidential candidate Mitt Romney making dismissive comments about nearly half of American voters — the 47 percent. Mother Jones saw a $100,000 online fundraising windfall, an upswing of 7.7 million page views in one week, and 22,000 new social media followers on Facebook and Twitter combined.

To make the case for investigative journalism to its readers, MoJo honed its brand identity around aggressive journalism. Back in 2006, when Bauerlein and Jeffery took over as co-EICs, they leaned into the slogan of “smart, fearless journalism” in addition to “a magazine for the rest of us.” This slogan is still in use today and often quoted as part of MoJo’s marketing materials. When MoJo talks to readers about fundraising, its appeals often come from journalists, who explain their work and how reader support makes it possible.

In recent years, Mother Jones has developed a new approach to talking with readers built on the values of journalism and the future impact of news coverage. The organization began educating its audience that the core of MoJo’s business model is the fundamental value and public service of the journalism Mother Jones produces. Indeed, the organization reimagined fundraising and donor relations as “reader support” and subscribers as “supporters.”

This growing emphasis on journalism — as a public service for the benefit of readers — created a symbiotic relationship between the editorial and business sides of the organization, elevating the pitch that the stronger the business, the stronger the journalism, and vice versa.

On the business side, this led to a more convincing digital consumer marketing strategy. Mother Jones’ fundraising team started responding to the news and events of the day with specific, targeted fundraising pitches. For instance, in February 2015, former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly dedicated part of his talk show to take issue with a Mother Jones story that questioned his coverage of the Falklands War. Within days, MoJo sent a fundraising email to its readers, highlighting O’Reilly’s response to its investigative reporting. Over the course of one week, they raised an additional $50,000.

“It’s outrageous, and I hope you’ll consider donating to Mother Jones right now,” said the fundraising email, referencing claims by O’Reilly. “Let Bill O’Reilly know that we will never let personal attacks stop us from doing what you — our readers and supporters — expect from us: producing smart, fearless journalism.”

The stronger pitch around Mother Jones’ brand of journalism reinforced the organizational alignment around investigative reporting. In fact, Mother Jones’ fundraising materials consistently identify the hiring of journalists as its top priority. Not only does this bolster journalistic efforts, it also strengthens the marketing pitch. The percentage of total Mother Jones editorial staff hovered around 50 percent in 2013-2014 and 2014- 2015, and as total staff and budget grew in 2016-2017, so did the percentage of editorial staff, reaching 60 percent of total staff. Between 2013-2014 and 2019-2020, MoJo saw its editorial staff expand by 37 percent and the entire organization grew by 22 percent.

As the focus on investigative news was building, Mother Jones also was extending its newsroom’s reader focus through the rest of the organization.

Having a close relationship with readers was a part of the organizational culture from the magazine’s beginning, with the slogan, “a magazine for the rest of us.”

“It’s what we’ve often described as having been baked into our DNA right from the very first issue of the print magazine: having a tight, intense relationship with our readers,” said Steve Katz, publisher of Mother Jones since 2009. “Without this, the magazine would’ve never succeeded — and that’s absolutely true to this day on the digital side. We think this organizational culture/identity was one key precondition for success in making the digital transition.”

By 2015, Bauerlein moved into the role of chief executive officer, and Jeffery became the sole editor-in-chief of Mother Jones. As CEO, Bauerlein doubled down on the “reader focus” strategy across both business and editorial sides of Mother Jones. While in 2019 this may seem an obvious strategy, as more news organizations lean into membership programs and nonprofit business models that rely heavily on readership support, five years ago it was still a novel concept in an industry caught up in online advertising and subscription models. Bauerlein believes that too often journalists make choices based on what they themselves think is good, rather than following readers’ preferences. “Journalism exists only as much as there is an audience engaging with [the work], large or small,” said Bauerlein.

She had tradition to build on: the founding mission and reporting ethos rooted in serving readers and financials that included direct-mail fundraising to readers. Bauerlein began extending that strategy to place readers’ needs at the forefront of both journalistic and financial decisions. And the strategy became strikingly visible through Mother Jones’ marketing and all the ways it communicated with readers from both the newsroom and the business office.

The reader focus led to a change in external messaging strategy, speaking directly to the readers about journalism in a personal, relatable way. An old appeal to readers from 2015, before Mother Jones made its messaging pivot to talk directly to readers about the journalism it produced for them, illustrates how far MoJo’s marketing has shifted:

“URGENT: Please donate $5 to nonprofit Mother Jones. (That’s like the cost of buying coffee for one of our reporters.)”

Compare that language with a more recent appeal by DC Bureau Chief David Corn, who wrote, “ … But we can only do this journalism if readers like you have our back, and I hope you’ll part with some of your hard-earned dollars and support our work today. I’m no fundraiser, but I know you want your contribution to have a big impact… ”

Brian Hiatt, director of marketing and membership at MoJo, said an important reframe around MoJo’s messaging strategy is that fact-based independent journalism is the cause, not Mother Jones’ budget. “When our fundraising took an approach that was more in line with our journalism, we were able to give it more prominence on the site,” said Hiatt, who first joined the organization in October 2014.

The second major change was the development of a new type of story, the “reader support column” column by Bauerlein and Jeffery. The two together, as CEO and EIC respectively, began covering MoJo’s fundraising in 2015 as a reporting beat with hard-hitting transparency. They moved fundraising appeals from traditional advertising formats to the “article” format on MoJo’s website.

In the past MoJo’s own fundraising appeals would compete for space on MoJo’s website with the advertisements sold by the ad team. “It finally hit us that our fundraising pitches are not advertising,” said Bauerlein. “They are content, and they should be articles. We wrote longform articles, took all the messages out of ad spaces, got rid of internal competition, and better aligned the form with what we wanted to communicate.”

As detailed in the Introduction, MoJo published its first reader support column in October 2015 as a way to explain a recent, expensive lawsuit the organization had fought. The headline read, “We Were Sued by a Billionaire Political Donor. We Won. Here’s What Happened.” Following its success, Bauerlein and Jeffery published a new column in December 2015 for their end-of-year campaign that launched a high-level conversation with readers about how Mother Jones’ journalism and business model work, with the headline, “There’s One Piece of Democracy That Fat Cats Can’t Buy,” and the subheadline, “At least so long as you do your part.”

Other media organizations are starting to make their own versions of the reader support column. For example, in September 2019, A.G. Sulzberger, publisher of The New York Times, wrote an opinion column with the headline, “The Growing Threat to Journalism Around the World.” Educating the reader about journalism and why it matters is increasingly part of the job of media.

In the past four years, Bauerlein and Jeffery have leveraged their reader support columns to promote a major investigative feature with the reader support column on the same webpage, as a way to underline MoJo’s journalistic chops and impact. With the headline, “This Is What’s Missing From Journalism Right Now,” MoJo’s fall 2016 campaign reader support column unpacked what was required to pull off journalist Shane Bauer’s investigation inside a private prison. The 18-month investigation cost the news outlet $350,000 to produce. In the course of about six weeks, readers donated $372,000.

The reader support columns are not static. Bauerlein and Jeffery post “updates” after their initial publication date, with fundraising totals and relevant news that highlights MoJo’s impact. For the reader support column highlighting Bauer’s investigation, they included an update that reads: “Now comes news that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) will reexamine its use of private prison companies to hold immigration detainees. This is a BFD — nearly three-quarters of immigration detainees are held in privately- run facilities.”

Finally, MoJo staff hold business content, namely fundraising materials, to the same standards as news content. They fact-check their material and post corrections when needed. “All communication goes through the same process and comes from the same sense of values,” said Bauerlein. “The content is content,” she said. “It’s not separate.” This approach keeps editorial and business messaging bound together in a tightly woven narrative.

This is one arena in which Bauerlein’s background as a journalist serves her well, as she is the one who writes the copy for pitches and campaign material. The fluid exchange between the business and editorial sides, often described as church and state in journalism-speak, is a clear strength for Mother Jones. By sharing the work of fundraising, the entire organization is oriented around the goal of raising money to serve readers. “As a nonprofit news organization, you cannot operate as if the journalistic side is separate from the value proposition,” said Bauerlein.

To maintain journalistic independence, Mother Jones follows guidelines established by the Society of Professional Journalists and by the Institute for Nonprofit News, and leaders have crafted specific policies for advertising and donations.

Right around the time they began developing their message about journalism as a public good, the leaders at Mother Jones borrowed the structuring toolkit of “campaigns” from the nonprofit fundraising playbook.

“There’s a distinction between strategy and campaign,” said MoJo Publisher Steve Katz, who came to MoJo from Earthjustice, which describes itself as a premier nonprofit environmental law organization. “The campaign is a tactic or a container for the strategy. It’s a marketing tool. The strategy is the fundamental assessment of internal strengths and opportunities and context in which we’re operating.”

Katz joined the organization in 2003 as Associate Publisher with a mandate to reinvent fundraising at Mother Jones. His immediate goal was to alleviate funding pressure on the board, and his long-term goal was to use nonprofit business strategies beyond journalism’s traditional advertising and subscription revenue streams. The news organization was founded as a nonprofit organization and has proudly maintained that status over its 40-plus years, relying on a mix of commercial revenue from advertisements and subscriptions and non-commercial revenue, in the form of philanthropic donations. Between 2003 and 2008, Katz established a robust membership team by combining the operations for subscriptions and direct mailing and investing in outside vendors to professionalize these services. He also began building relationships with major donors to grow the revenue stream for major gifts, and he helped the organization develop its campaign methods. The magazine kept print circulation flat, choosing instead to invest in digital reach, which increased roughly 20fold during this period as a result of the organization’s new content and audience strategy.

Bauerlein describes the “magic” of bringing together the structure of the campaign with the deeper, sophisticated messaging around journalism. “You can do campaigns anytime and anywhere,” she said. “You can put a blast on the site and emails and have a goal for it, and you have a campaign … [What’s different here is] taking that campaign structure and filling it with a message, in the voice of the journalist and [that] is about the journalism and ties to current events.”

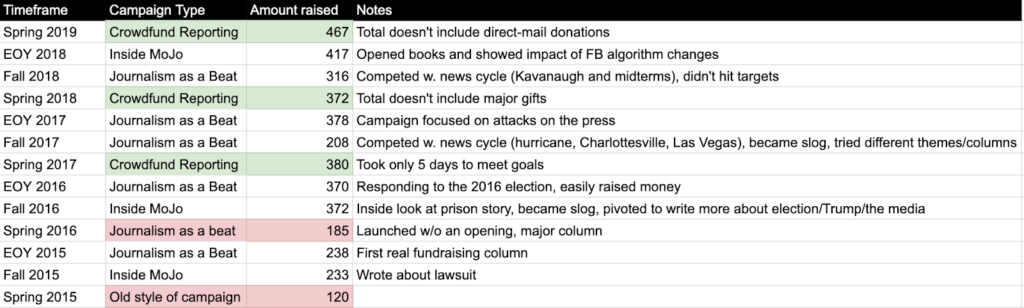

For Mother Jones, there are two types of campaigns — seasonal campaigns and institutional campaigns — which differ in scope, duration and purpose. Seasonal campaigns come up three times per year and respond to the news cycle and related reporting opportunities, each raising dollar figures in the six digits. Institutional campaigns run over several years and reflect the organization’s long-term goals and vision, raising between $3.75 million to its current goal of $25 million.

The campaign as a container provides three major benefits:

It has proven to be an effective tool for raising money; it bolsters the organization’s planning and direction; and it supports MoJo’s broader mission to tether its business model to its journalistic impact.

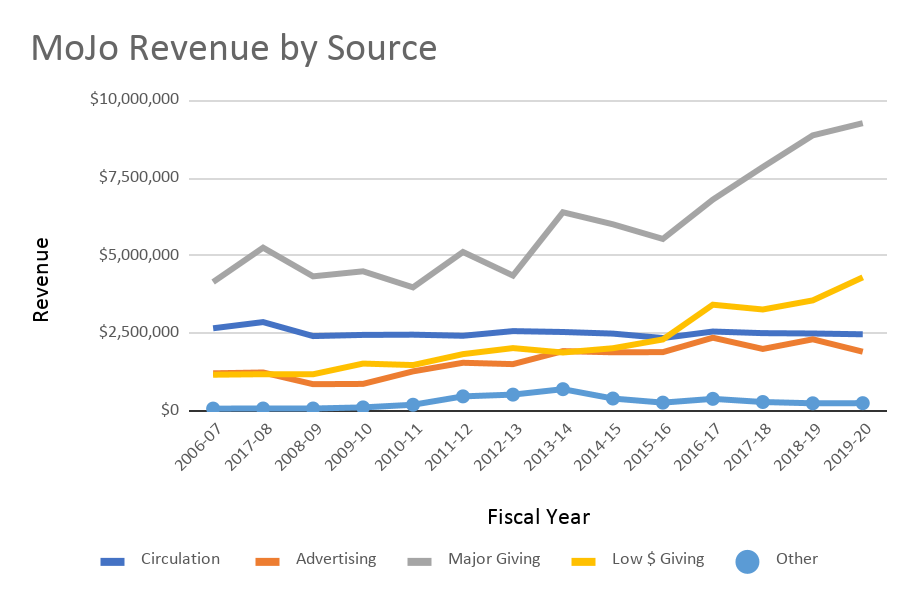

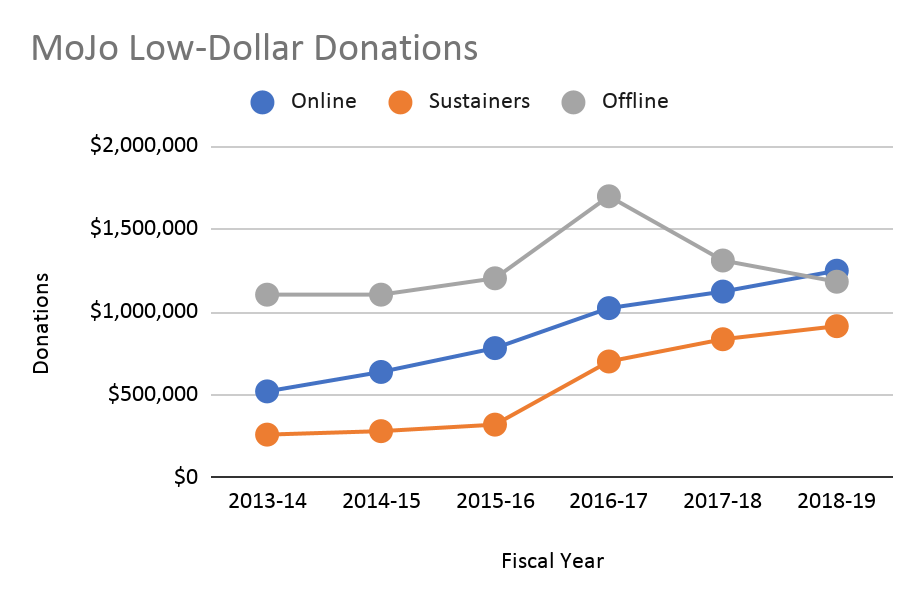

With the help of campaigns, both low-dollar donations and major giving have increased, allowing MoJo to develop more stability and expansion in staff and reach. For 2019- 2020, low-dollar fundraising totalled $4.3 million, nearly outpacing advertising (at $1.9 million) and print magazine subscriptions (at $2.5 million), combined.

Low-dollar donations have played a larger role as seasonal campaigns became a bigger part of Mother Jones’ strategy. One-time, low-dollar online giving has more than doubled in six years to $1.25 million in 2018-2019 from $522,000 in 2013-2014. During an average non-campaign month, MoJo might see about $30,000 in low- dollar giving. In a typical campaign month with more aggressive site asks and emails, MoJo sees $200,000 to $400,0000 in donations. Large donations remain critical to institutional campaigns, which raise bigger sums of money. Major giving, built on personal asks and one-on-one relationships, represented 68 percent of all giving in 2019-2020. As part of its increased focus on “reader-supported journalism” as the message, the organization also began promoting the importance of sustaining (monthly) donations, which resulted in a significant increase in sustaining gifts from online readers.

Together, the two types of campaigns create a roadmap for both short- and long-term planning. Seasonal campaigns require short-term, strategic planning months in advance. These campaigns sometimes “crowdfund” around specific journalism priorities, making it clear for staff and readers alike what the organization’s priorities and goals are. MoJo’s most successful campaign — in that they hit their fundraising target within five days — raised $380,000 to dig deep on the Russia scandal in spring 2017.

Institutional campaigns require long-term, strategic planning over the course of several years. Mother Jones first piloted a major institutional campaign in 2006 called “Mother Jones 2.0,” which raised $3.75 million over three years. Over the past five years, MoJo has been focused on a more ambitious fundraising campaign, unprecedented in the nonprofit news space, called “The Moment for Mother Jones” with an aim to raise $25 million by the end of 2019. It is structured around five strategic priorities: editorial expansion, technology, modernization, revenue growth, training and engagement/impact. For instance, the Moment campaign earmarked $2.2 million for “Priority 4”: expanding MoJo’s training program. The campaign outlined steps toward this goal, which include: expand fellowships to all bureaus and departments, increase financial support for fellows, develop fellowships at pre-college and college level, create residencies for mid-career professionals, and make available other training opportunities in the industry.

“This [Moment] campaign is the first of what I have no doubt will be many such campaigns from other nonprofit journalism organizations in the near future,” said Katz, MoJo publisher. “I know of two organizations that are already headed in this direction and have turned to us for advice on our experience.”

As a third benefit, campaigns strengthen and stabilize the connection between readers and MoJo, as the campaign framework trains the public to see journalism as a public good akin to other civic institutions. “What my job is really, is to make the case that journalism is a public good, just like a symphony, that part of a good community is vibrant journalism,” said Katz.

Framing journalism as a public good also helps MoJo avoid excessive reliance on any particular one story or project, further protecting its business. Aside from the 47 percent story about Romney in 2012, MoJo’s spikes in donations have not come off any specific, big scoops. “We generate those spikes with deliberate, strategic appeals that explain the value (and values) of our journalism,” said Bauerlein.

Leaders at Mother Jones continually tried out new ways to attract donors, such as leveraging planned commitments as matching opportunities and promoting regular monthly “Sustainers” donations online. “These were not primarily prompted by user signals but more by wanting to adapt, grow, and innovate rather than being content with what we were doing,” said Bauerlein.

Multiple subjects to engage readers: Different genres of seasonal campaigns, as defined by this case study analysis, ask for support of different beats.

The “Crowdfund Reporting” campaign asks for donations to support the reporting of a specific subject. For example, a campaign focused on corruption reporting raised $467,000 in spring 2019; a campaign focused on disinformation reporting raised $372,000 in spring 2018; and, a campaign focused on the Russia scandal raised $380,000 in spring 2017.

Then there’s the “Journalism as a Beat” campaign, which helps readers better understand threats to journalism and asks for donations to fend off those threats. The “There’s One Piece of Democracy That Fat Cats Can’t Buy” campaign, from the end of 2015, raised $238,000. The “It’s a Perfect Storm for Destroying Journalism” campaign raised $378,000 in late 2017.

Finally, the “Inside MoJo” campaign goes deeper on MoJo’s spending, budget and decisions and explains why the organization needs reader support. For example, the “We Were Sued by a Billionaire Political Donor. We Won. Here’s What Happened.” campaign from fall 2015 raised $233,000 in low-dollar donations. In “It’s the End of News as We Know It (and Facebook is Feeling Fine)” campaign, MoJo opened its books and showed exactly what Facebook’s algorithm tweaks meant for MoJo. That campaign, from late 2018, raised $417,000.

Multiple formats to reach readers: Offline (direct mail and phone) and digital fundraising efforts operate independently, though content and strategy are coordinated. A digital campaign generally kicks off with a reader-support column, then moves on to direct emails from reporters, such as DC Bureau Chief David Corn. MoJo keeps up direct pressure with spots on every webpage that are tweaked and iterated based on response and events in the news. When the campaign slows down, new columns and subject pivots are employed to revive the campaigns. The reader-support columns often provide fodder for direct-mail appeals and phone scripts (not necessarily at the same time as a digital campaign), which are also subject to iterative improvement on the longer time scales of print production. The messages are reworked and repurposed yet again for both digital and mailed appeals to MoJo’s major gifts and advancement (intermediate) donor lists.

Multiple ways to donate: MoJo ensures that there are multiple entry points and opportunities for giving, with digital (email and website) and offline (direct mail, phone) messaging. Messages come with customized “gift strings” allowing donors to select various levels of giving; donors are also encouraged to consider giving as sustainers, use different payment systems (e.g. PayPal), and have options such as giving gifts of stock, legacy gifts, or giving from donor-advised funds.

Multiple times per year: With at least three campaigns a year, MoJo can play off current events and the cycle of typical giving. The spring campaign starts in April or May; the fall campaign launches typically in September; and the end-of-year campaign begins in December. End-of-year and springtime campaigns are typically most successful, while fall campaigns struggle the most, competing with a busy news cycle.

Experimentation plays a major role in Mother Jones’ sustainability. A habit of testing new approaches with small bets is particularly pronounced with social media and engagement. When considering projects and opportunities, once MoJo commits to a project or new experiment, they avoid a waterfall model of planning and instead apply a minimal approach to whatever they are planning. In other words, they spend one week on an idea rather than go through a six-month planning process.

For example, MoJo is currently testing sponsored content with two paid posts, rather than building out a broader strategy. They also tried out Facebook Live and found it was mildly successful, but wasn’t worth being part of their major strategy because neither the end product nor the reader response was substantial.

“Facebook Live came around, and we felt like we should try it,” said Ben Dreyfuss, editorial director for growth & strategy. Dreyfuss joined Mother Jones in 2013 to run the organization’s social media accounts. “It turns out it wasn’t great enough that we were happy enough with it.

Another example is the recent expansion of news blogging on the MoJo website to take advantage of the wave of impeachment news around President Trump. From an audience-development perspective, the goals of the blogs are to increase the number of posts people are producing without cannibalizing other content and to raise site traffic.

“If it’s not working after two weeks, we’ll try to fix it a few times. But it’s not going to take three months to kill it,” Dreyfuss said. “The most important thing I’ve done is make it clear that reporters and editors can publish whatever they want, but if they want it on Facebook or Twitter, they need to think about how it will engage a social audience. That carrot and — it is like being a front page editor.”

MoJo constantly redesigns social content to fit reader preferences. To prompt stickiness as smart, conversational and relevant, MoJo mixes up the content and tone of its engagement strategies. On social media, they think in terms of long-term story arcs, iterative story coverage, and news of the day. “Whenever we publish stories, we come up with like 10 different headlines,” said Dreyfuss. “One of the first things we do is tweet them with different UTMs to see if one vastly over-performs. We A/B test them. And then we change the actual post. There are clear wins.”

To function in a flexible way, Dreyfuss takes on initial pilots himself, then once all the kinks are ironed out, he passes on the work to the rest of his team. “When things become successful enough, I hand off the work and run somewhere else,” said Dreyfuss. “For Facebook, that’s what happened. I was packaging stories and writing every headline for Facebook and changing the art and making sure algorithms were working. I was doing the testing. Eventually it becomes big enough that there’s a system improvement … I can train someone on how you do it, then move on to something else.”

Dreyfuss, who is based in New York, relies heavily on a social team of three to feed social platforms while also developing new strategy. His deputy, a news and engagement editor in London, focuses on Facebook and Twitter and also serves as a breaking news reporter. When his deputy in London logs off, an assistant editor in San Francisco begins managing MoJo’s Facebook and Twitter accounts. Meantime, a digital media fellow in New York writes and reports on subjects that Dreyfuss believes will perform well on social media. Dreyfuss also works closely with a digital media fellow in New York, who handles Instagram for Mother Jones.

It’s critical to embrace each platform on its own terms; to be prepared to change your metrics for success and to engage the editorial team, according to Dreyfuss.

On Instagram and Twitter, shares and engagements have become more important than total referrals as MoJo focuses on reach and impact more than monetization on those platforms. “You have to watch the behavior on the [specific] platform,” said Dreyfuss. “Twitter is a publishing platform for people. Facebook is like a yearbook. Once you recognize that [difference], there are ways of playing to it. We’re not treating all platforms the same.”

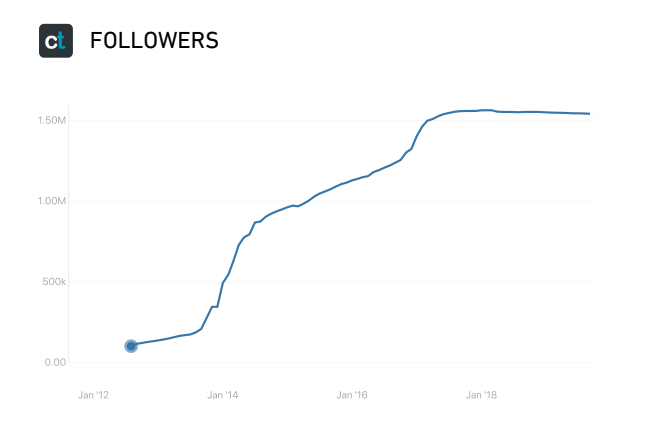

When Dreyfuss joined MoJo six years ago, he focused on growing the organization’s followers on Facebook. Once the list of followers grew to a substantial number that could essentially maintain itself through the network effect of sharing online — what Dreyfuss calls “viral lift” — he pivoted his focus to drive people to MoJo’s website. This meant that the Facebook audience stagnated, but referral traffic to Mother Jones started to grow.

Dreyfuss also considers two audiences in his engagement work: the readers and the reporters. “It’s not just how to get people to do things as readers but also getting those stories made, to motivate people in a certain way,” he said. An example of this is getting reporters and editors excited about high engagement numbers on Instagram.

At times the prioritization of audience preferences can supercede monetization forecasts. Mother Jones opted into Apple News+ because readers are there, not because it’s necessarily a good business proposition. MoJo moved onto Instagram because readers were there, not because they had a business model figured out in advance for it. “It’s not necessarily our decision to make in an ivory tower whether we’ll be there for them,” Bauerlein said. To check themselves, they ask: Does it score high enough on serving an audience that it could also eventually serve the business?

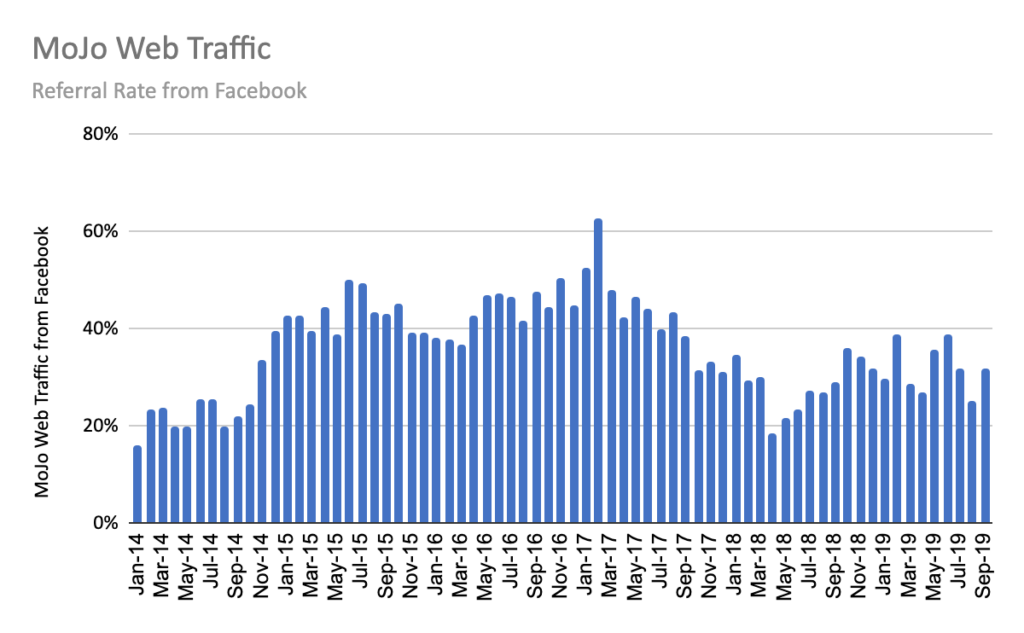

This is especially relevant as news organizations work to become less dependent on third-party platforms like Facebook or Google in order to protect themselves from outside volatility. In 2014, 24 percent of web traffic to MoJo’s website on average came from Facebook. Over the course of the next three years, that number grew to an average of 44 percent, peaking at 63 percent in February 2017, before beginning a steady decline. By August 2019, it had dipped to 25 percent.

After gaining a critical number of Facebook followers, MoJo stopped focusing on growing Facebook followers and pivoted to increasing its referrals to its website from Facebook.

The leaders at Mother Jones anticipate a handful of major challenges on the horizon and fully expect the news outlet to keep evolving to meet the changes at hand. These challenges essentially whittle down to two external and two internal areas of change.

Most immediately, it’s hard to predict how the upcoming U.S. presidential election will impact news organizations’ fundraising. Many news organizations enjoyed what became known colloquially as the “Trump bump,” following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, as issues of misinformation and inaccurate news put a premium on quality journalism. For Mother Jones, the 2020 U.S. presidential election looms with uncertainty for its impact on the organization’s fundraising projections.

Brian Hiatt, who directs digital membership and marketing, said that launching the 2019 Corruption campaign was one effort to address the election, with the aim to improve step-back, investigative election coverage that makes MoJo’s impact self-evident. This way, regardless of the election outcome, MoJo can point to quality investigative reporting that proves MoJo’s unique value proposition and makes the case for donating that much easier.

“How you handle elections is hard because you don’t know how it’s going to shape up,” he said. “We are focusing on differentiating what you are able to do as a nonprofit, instead of just covering the horse race … The election is a magnifying glass that comes around every four years. Do everything to be your best self and adapt and adjust as things unfold.”

A second challenge is the current climate of misinformation and disinformation and how it is redefining the media’s relationship with readers. A survey of Americans conducted in November and December 2018 by Pew Research Center found that 48 percent of respondents said they had a “great deal/fair amount of confidence” in the news media, and 61 percent said that news media “intentionally ignores stories that are important to the public.”

Given the need for new strategies to address attacks on the press, Bauerlein believes that journalists need to learn more about organizing from industries that have harnessed community support in the past.

“If we’re looking to the audience to rally and save journalism and become the bedrock of engagement, financial support and conversation, and political support in the face of threats to freedom of the press … we have to become much better organizers,” she said.

Pivoting to internal challenges, a third shift is around staff and talent. Swift changes in journalism have required new roles in the field, and more leadership training is required. An evolving vocabulary for journalism roles has cropped up in the past two decades, such as “product manager” and “engagement specialist” and “director of partnerships.” As the world of nonprofit news continues to codify, there’s also a growing demand for entrepreneurial journalists to become newsroom leaders of the future.

To build a pipeline for media entrepreneurs, MoJo has aspirations to borrow from the success of its fellowship program for budding journalists and to create a similar fellowship program for media entrepreneurs. Bauerlein said that for nonprofit news, it’s especially important to find business-minded people who are committed to the mission, not to profit.

“I think we’re going to continue to find these people among journalists who have an entrepreneurial bent,” said Bauerlein, who mentioned Ben Dreyfuss, the engagement and social media leader at MoJo, as an example. “His role has become a hybrid of very straightforward editorial and newsroom work but also [he’s] trying to figure out how to mobilize readership support and how to relate to a platform like Facebook.”

A fourth and final challenge to Mother Jones is keeping its fundraising on campaign footing. Organization leaders are already looking into what the nature of the next revenue push will look like, and MoJo’s publisher Steve Katz said that he sees the organization’s 50th anniversary in seven years as a pivotal moment for new fundraising.

Distinct from Mother Jones’ planning with its board, and thinking of the industry more broadly, Katz is also mulling over new, creative sources of capital for news organizations that focus on growth rather than simply paying the bills. He noted that it is difficult for MoJo as a nonprofit news outlet to access affordable investing funds. “We’ve tested the waters of using the Moment campaign as a philanthropic source for investment and growth but there’s really not a marketplace for journalism NGOs (non-government organizations) to go to for financing,” said Katz. To develop sound financial footing, Katz said he is brainstorming the sustainability benefits of an endowment and described it as “the next transformative step for us.”

About the Author: Caroline Porter is a journalist and media strategist. Her consulting work largely focuses on business models for journalism, working with media companies, academic institutions and others on subjects such as newsletter strategy and partnership models. Prior to launching her own consultancy, Caroline worked as a staff reporter for The Wall Street Journal in the Chicago and Los Angeles bureaus, serving as the national K-12 education reporter. She has also produced animated videos on news literacy and served as an adjunct lecturer at Northwestern University’s Medill School. Most recently, she produced an audio program on homelessness in Los Angeles and Berlin for The Big Pond, a podcast from the Goethe Institute and distributed by PRX.

About the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy: The Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy is a Harvard Kennedy School research center dedicated to exploring and illuminating the intersection of press, politics and public policy in theory and practice. The Center strives to bridge the gap between journalists and scholars, and between them and the public. The Center advances its mission of protecting the information ecosystem and supporting healthy democracy by addressing the twin crises of trust and truth that face communities around the world. It pursues this work through academic research, teaching, a program of visiting fellows, conferences, and other initiatives.

The Institute for Nonprofit News supports a network of independent, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more about INN.

Back to top