By Tim Griggs

May 21, 2018

Co-published by the Institute for Nonprofit News and the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. Produced with the generous support of The Knight Foundation. The full report is available for download.

To editors and executive directors of nonprofit news organizations, Anne Galloway’s story will sound familiar: An experienced local newspaper editor, set adrift in a round of layoffs, starts her own nonprofit digital news enterprise, learns business skills on the job, produces community-changing journalism, and works herself to exhaustion in the process.

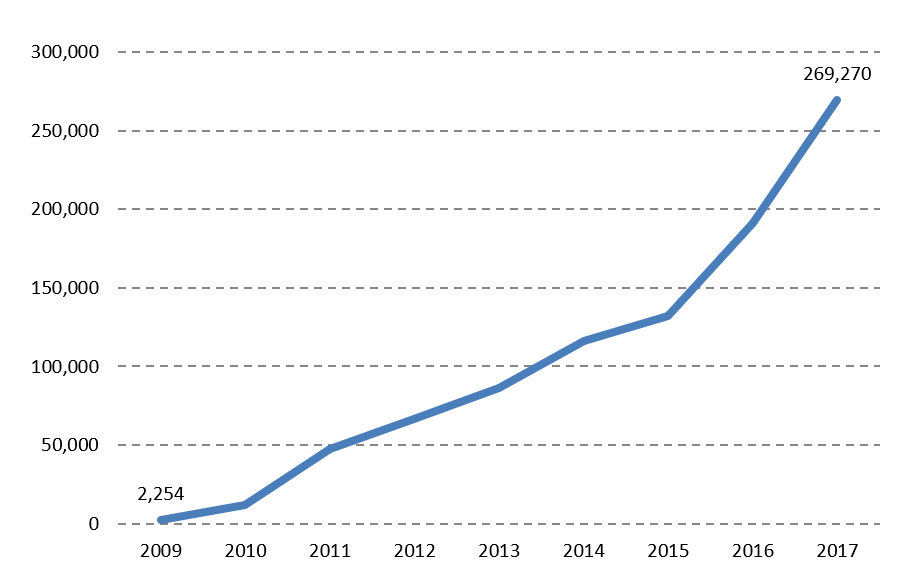

But Galloway’s story is remarkable. She turned the idea of a small state-focused news startup in Vermont into an inspiring enterprise with growing audience, staff and revenue. In the second least populous state in the country, VTDigger is averaging nearly 300,000 monthly users, has a staff of 19 full-time employees and an annual budget over $1.5 million.

The past few months have felt like something of a moment for VTDigger.

Its three-year, 250-stories-and-counting exposé into alleged fraud at the Jay Peak Resort has stamped it as a major investigative force in the region. It hired the first-ever Vermont-focused D.C. bureau chief to cover the state’s delegation in Washington. It has been featured in the Columbia Journalism Review, NiemanLab and The New York Times as a new model for success in the nonprofit news movement. And it has secured a multimillion-dollar investment to dramatically improve business, technology, and reporting to bring it to a new level of sustainability.

It is, in some ways, the envy of the nonprofit news world, with robust growth in audience, editorial impact and revenue.

But Digger’s success is far from an overnight sensation. It has toiled for years with the same obstacles faced by peers at local, state, and topic-based nonprofit news sites. They are generally undercapitalized and understaffed ventures, filling a clear gap in reporting vacated by legacy publishers but with a tenuous-at-best shot at long-term survival.

So why has Digger succeeded where others have not? What can we all learn from Digger’s accomplishments? What makes it unique and what makes it replicable?

This is Digger’s story, with some strategy lessons broken out for those involved in, supporting, or studying nonprofit news.

An institution often adopts the personality of its leadership. For Digger, the similarities are striking. The organization, like its founder, is intensely passionate about the mission and dogged in pursuit of both watchdog journalism and sustainability. Meet the Digger staff and you’ll immediately see it: They, like Galloway, embrace the grind.

Galloway is soft-spoken, unassuming, egoless. In her own shop you might even overlook her. But friends and colleagues are clear: She’s the hardest worker they know.

That may stem from her background.

At 10, her parents became part of what she describes as a cult-like fundamentalist Christian movement that equated intellectual pursuits with witchcraft. The family moved from central Ohio to Kentucky, where she was enrolled in a tiny private school. When she could, she read The Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, then the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, and “snuck in some NPR when they weren’t around.”

Hard work was always expected. She sold tennis shoes in high school and picked up odd jobs to pay for college — at the loan desk at the campus library, making copies on the graveyard shift at Kinko’s. At the University of Kentucky, she volunteered for the student newspaper.

After graduating in 1987, she met her future husband (then an architecture student at UK), got pregnant, and moved in with her husband’s family in Vermont. Galloway went to the local newspaper — The Hardwick Gazette — and, based on her student newspaper clips, was hired on the spot.

“There was a fire on my first day of work and I had to go out and cover it,” she said. “I was so shy and felt so embarrassed making these calls and talking to people I’ve never met. It was terrifying. But I loved it.”

Despite the hook of journalism, reporters’ hours aren’t necessarily conducive to life with a baby. So she went to work in the local school system, teaching basic life skills to high school students with severe learning disabilities — and then moved to New York when her husband was accepted to Columbia’s graduate architecture program. There she worked in Butler Library, microfilming books. After Galloway’s second baby arrived and her husband graduated (on the same day), the family moved back to East Hardwick, where she started freelancing art reviews for a new tabloid newspaper, Seven Days.

For a few years she bounced between jobs — freelance writing about local arts, proofreading, potting plants at a nursery, and writing the newsletter at the Nature Conservancy. Galloway eventually found her calling on the Sunday desk at the Times Argus in Montpelier, where she worked every Saturday and every holiday for 10 years, eventually becoming the Sunday editor.

“I got that job through attrition,” she said. “(The staff) kept getting smaller and smaller and I was one of the few people left.” She led a series on how climate change was affecting roads during ski season, which won a New England Press Association award. An IRE workshop gave her the investigative reporting bug, and she pushed an already overworked staff to go deeper.

In January 2009, 16 people were laid off, including Galloway.

“I was devastated since I’d finally found my North Star,” she said. “I finally knew what I wanted to do and didn’t have a newspaper to do it.”

Galloway was at a crossroads: Her family had no interest in leaving East Hardwick and she had no interest in doing anything other than investigative reporting.

“It was clear to me that there wasn’t really good coverage of issues in Vermont. I thought there was a need long before I started Digger. People would complain that we weren’t getting to the bottom of things — and we weren’t. Getting a pink slip was the trigger; it hadn’t occurred to me that I could start something on my own.”

Starting a news organization from scratch, and without the backing of a wealthy supporter, would prove to be the hardest work imaginable. But, she said, there was simply no other choice.

This was 2009, a wretched year for the news business as the recession further battered an already beleaguered newspaper market. Galloway knew this wasn’t a blip; news organizations would continue to hemorrhage staff and consumers would continue to migrate to digital platforms. She also felt strongly that building a nonprofit enterprise was the right approach. “There are no profits to be had in media, so what’s the point?” she said. “So many newspapers have mission drift. It’s more about profit than about helping communities.”

She called around asking for advice from early nonprofit startups. Paul Bass of the New Haven Independent in Connecticut let Galloway’s concept live under his Online Journalism Project’s 501(c)3, which was designed to encourage the development of professional-quality local and issue-oriented online news sites.

A Vermont small business development center helped Galloway put together a business plan and gauge interest. “They urged us to be very clinical about this,” she said, because her passion wouldn’t matter if there were no demand for her product.

“I literally went around with a clipboard and asked people what they thought of it and called about 100 people — businesses, readers, journalists. About half said they thought it would work.”

She also created a spreadsheet of every nonprofit news site she knew at the time, and charted what they were providing and how they raised money. She thought about what might work in Vermont, talked to potential readers, and learned about their likes and dislikes.

Strategy: Understand the market

This formative stage is a critical — and often skipped — step for any startup. What’s missing? Is there an actual news need? If so, do you have the skills, platform(s), and capacity to fill it? Is there money to support it? If so, from where? The standard business plan approach forced Galloway to take her feelings and preconceived notions about the need for enterprise and investigative reporting in Vermont out of the picture and think objectively about the market for that product.

She raised $12,500 in startup funds — seed capital would be a grandiose description — from three regional foundations and forged ahead. “I had no sense that I’d get another dime,” she said. “I just blundered my way through it. I was obsessed with the idea and would’ve walked through fire to do it.”

VTDigger.org was born on August 31, 2009.

Galloway spent her earliest funds on two things: web development and freelance reporting. One thing she didn’t spend money on? Herself. Galloway went two years, working 80-90 hours a week without a paycheck. She says this makes her husband, Patrick, one of the real heroes of the story. “He has been a stalwart and long-suffering supporter,” she said. “He came up with the name, the logo design, and has been a key adviser about the people side. He jokes that I should put him on the payroll.”

In late 2009, Digger was posting about two stories per week, mostly long-form state policy coverage. Galloway was building out her site to be more than a blog and trying to figure out how to raise money.

Meanwhile another startup, the Vermont Journalism Trust, was charting its own course. Its original concept — to fund independent reporting that could be published in legacy media throughout the state — wasn’t getting the traction its founders imagined, in part because newspapers in the state were competitive by nature and leery of collaborating with anyone. The board reached out to Galloway in the spring of 2010.

They didn’t have much funding of their own, she said, but they pooled their resources to back Digger and leveraged their connections to foundations, prospective wealthy supporters, and the state’s business community. Galloway sorely needed that access because she was not a well-known reporter statewide.

“How can a girl from East Hardwick with an arts reporting background start an investigative news outlet? It was a logical question,” she said.

In October 2010, the two organizations and their boards merged. In March 2011, the Vermont Journalism Trust became the official publisher of Digger.

Strategy: Expand your network

You might not have an existing entity in the same market with a similar mission, like Digger and the Vermont Journalism Trust. But you will find local organizations — a community foundation, a library, a museum, a like-minded civic group — that can help you develop relationships with business leaders, philanthropists and others. It’s important to reach out to people in your community for support. Find the connectors — the people who believe in your work and who are connected to business leaders, philanthropists and others. Expanding your network is time well spent; Galloway gives talks about Digger and meets with people in the community two to three times per week.

Among Galloway’s early instincts was to avoid relying on foundation support alone. She envisioned an NPR-like mix, with underwriting, large donations, and memberships, all of which would need to be built from scratch.

As she set out to secure corporate sponsorships, reality set in. “I had to learn the lingo. I had to learn to sell,” she said. “Then you think you’re selling but you’re actually just begging.”

With little or no audience, infrequent content, and no successes to point to, Galloway realized a hard truth about sponsorship sales for nonprofit news outlets: In the early days in particular, you have to sell an idea or a vision. That’s a challenge even for experienced sales leaders, let alone an editor in unfamiliar territory.

But Galloway’s persistence paid off. Cabot Creamery, the dairy co-op, was the first taker. With a small but meaningful $7,000 initial investment, Digger was on the map.

Strategy: Start small

The classic “foot-in-the-door” sales and fundraising tactic is to ask for a small amount of money or a low commitment first, prove your value, and increase requests over time. Digger hasn’t changed its sponsorship pricing much (about $500 per week for run-of-site display) but over time began creating more custom campaigns. It added higher-priced packages including podcasts, paid posts, email newsletters, etc. Now, with years of practice and demonstrated value, it is better equipped to go after larger potential corporate sponsors in the state. “Now we’re elephant hunting,” Galloway said.

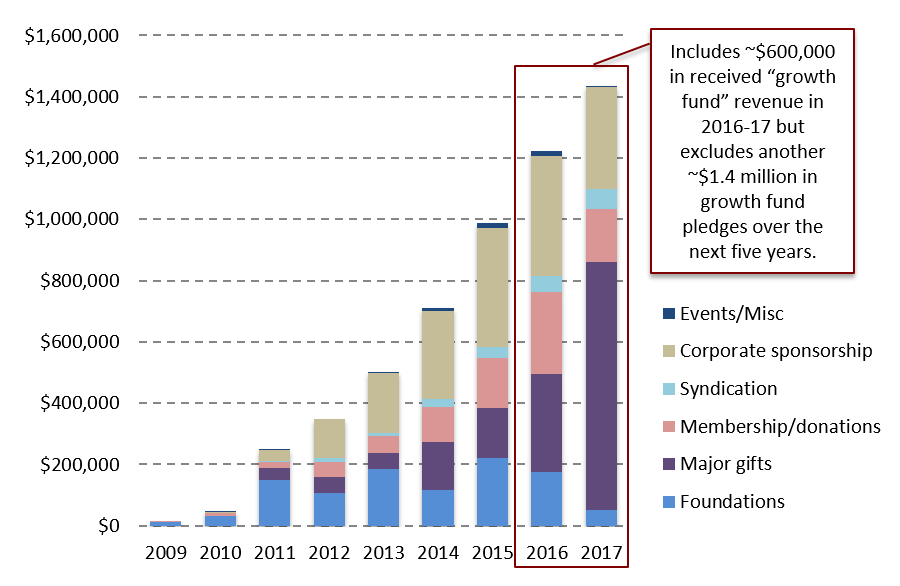

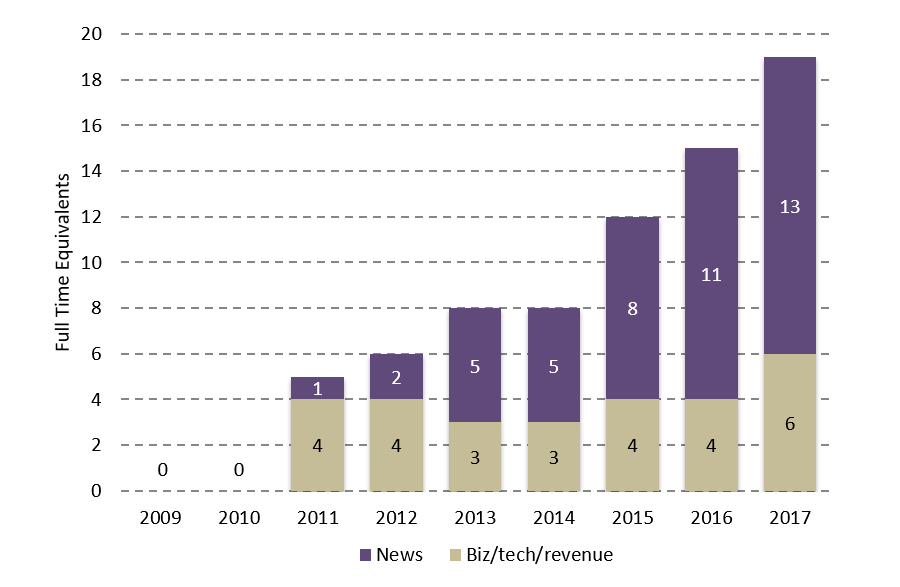

In 2011, thanks to support from several family foundations, readers, and underwriters, Galloway was able to begin paying herself and hired her first four full-time employees: a web developer, a reporter funded by a Knight Community Information Challenge matching grant with the Vermont Community Foundation, a business manager, and a sponsorship sales lead.

In the early days, Galloway took a measured risk and invested more heavily in operations, sales, and technology than in journalism resources. “I like giving up things I’m not good at,” she said. More reporting staff would come later.

Strategy: Prioritize business-side investments

Nonprofit news site founders often think they should invest all their time and funding in the journalism in their early years. They can end up hobbled by scarce resources far longer than founders who stretch to hire business staff or consultants. Early investment in business development is crucial to build and keep momentum around donations, sponsorships, and partnerships, and to create diverse revenue sources. These positions help sell the mission. Organizations that commit to business roles early on rather than having journalists try to do everything can grow further and faster and have stronger journalism as well. The proportion of spending on business and editorial resources in VT Digger’s year-over-year staffing is a model worth imitating.

In the beginning, Galloway wrote grant proposals and handled the rudimentary bookkeeping herself. But once the “donate” button on the site actually started bringing in money, Galloway quickly realized how much work that entails.

“As soon as I was able to raise enough money, I hired someone to handle thank you notes, manage donations, and take over accounting,” she said.

For her second hire, Galloway poached Michael Knight, a sales director and former colleague at the Times Argus, to take on underwriting. Knight, often with Galloway in tow, realized another challenge about the nonprofit news space: Local businesses didn’t necessarily get it. It’s digital only, which can be a foreign concept even today for some. And it’s mission-based; sites that sell only based on impressions will find the local ad game to be a very difficult proposition.

Businesses didn’t know who or what Digger was, although they appreciated the concept once they understood it.

Strategy: Invest in strong sales people

Good sales people for nonprofit news sites are hard to find because they need to understand both the mission and the medium. Digger’s first sales director, Michael Knight, came out of newspaper ad sales, so he was accustomed to being rejected. Its newest sales person, Christina Griffin, has experience in pharmaceutical sales, so she’s used to cold calls. “You have to know if this person has the capacity to blend mission and ROI and know in any given circumstance how they’re going to pitch a potential underwriter,” said Theresa Murray-Clasen, Digger’s director of underwriting since 2015. “You have to be very nimble and quick on your feet but also good at research — you really need a good understanding about what you might face when you walk in the door. And lastly, you have to match the product to [the sponsor]. You don’t want to pitch them on podcasts or video if they have no chance in hell of ever coming up with video content.”

Galloway and her team, from the earliest days, understood in theory the relationships between journalism, audience and revenue. But in practice they had a problem: Too few stories, not enough eyeballs, and not enough revenue.

In 2009, shortly after Digger launched, it became very clear that publishing only a couple stories a week would make it more difficult for Vermonters to develop a regular reading habit, and with a tiny portion of state residents as users they’d never be able to achieve their business goals. And, most importantly, they knew daily coverage would lead to better enterprise reporting.

So Galloway and her team of interns and freelancers began covering the state legislature — every day. Soon Digger was getting a little traction. By May 2010, the site had grown from zero to about 15,000 monthly users. A year later, traffic had tripled to more than 45,000 monthly users.

“You can’t just cover something once and expect change to happen,” Galloway said. “You have to cover things over and over again to show the iterative change over time. You get great investigative stories because you build trust with sources by reporting daily. And you get tons of tips so the next story is right in front of you.”

In addition to daily reporting, Galloway wanted Digger to be a platform for the community. She posted publicly submitted commentary and community-oriented press releases. The latter came with a bit of controversy, as the merger with the Vermont Journalism Trust gave Galloway a board of directors.

“The board thought, ‘Hey some of these have a lot of spin in them,’” she said. “And I thought readers know the difference and if we keep our stories separate, people will get it. Many were from government agencies about things like how to get a flu vaccine or from state police about major issues. Without any staff at that point, it was a way to expand our reach and provide a reader service.”

Strategy: Think carefully about quantity

There’s a vicious cycle for underfunded news startups: More frequent, high-quality journalism is more likely to attract the right audience, which costs money, which is harder to raise without frequent, high-quality reporting. Being mindful of the role quantity plays here is important. The Digger team made a conscious choice: Go daily as early as possible and encourage readers to develop a habit. Whether or not you choose to follow that path, understand the risks and rewards. Less frequent content allows you to start small and focus your resources on investigative reporting but may make it more difficult to grow audience and raise money. As audience and revenue grew, so did Digger’s ability to invest in journalism. In 2011, the site had a single full-time reporter. In 2012, two. In 2013, four. By 2018, Digger had 11 reporters and five editors.

In the early days, Galloway said, readers, businesses and potential funders recognized Digger’s coverage as fearless. “We published stuff every day that pissed off someone,” she said. “But you have to do something remarkable — you have to do more than just exist.”

There is a generally understood but often underestimated reality that some nonprofit news sites face: It can be a big challenge raising money for an enterprise with an investigative reporting tilt. How can you persuade business leaders and major donors to support you when you also hold their feet — and their friends’ feet — to the fire?

Galloway said it’s true that some big sponsors and donors won’t offer financial support because of Digger’s reporting. There are many others who understand this kind of journalism is essential for democracy and creates a more informed electorate. And, importantly, she describes quite a few supporters who originally balk at contributing to Digger but come around when they see that the site is unwavering in its aggressiveness.

“We tell people that we bite the hand that feeds us. We don’t pretend that it’s not a problem,” Galloway said. “Basically, if you have integrity and are true to your word and know that you’re principled and reporting for a reason — in other words, not out to get people but just doing the work as dispassionately as possible — then people understand you have a job to do and it’s not personal.”

In 2014, Digger first caught wind of potential fraud at Jay Peak Resort — one of Vermont’s top ski destinations and a major employer in the state — stemming from misuse of funds through the EB-5 visa program. EB-5 grants permanent residency to foreigners who invest $500,000 or more in U.S. businesses and create at least 10 full-time jobs.

The developers behind Jay Peak began with a vision to create a modern, four-season resort, but their ambitions grew to include commercial projects that would transform a sleepy county. Digger documented complaints from immigrant investors that the developers had seized ownership of the hotel at Jay Peak without their knowledge or consent, and that state officials with oversight of the projects had a tight relationship with the owner and CEO of the resort.

“Bill Stenger, the CEO of Jay Peak Resort, came to my office after the first story ran and, in a rage, wept in my office, insisting that everything was on the up and up,” Galloway said. “Then, shortly afterward, state officials attacked our credibility. We were out alone on the story. Other media outlets shied away from it, maybe because they felt we were going too far in questioning the conventional wisdom — that Bill Stenger and Ariel Quiros (Jay Peak’s owner) were bringing jobs to the poorest region of the state and who cared if some rich foreign investors got hurt.”

“We got so much pushback from state officials and the developers, I knew we were on to something.”

Galloway and her team were relentless in pursuit of the story. They found, through public records, that the Vermont EB-5 Regional Center hadn’t provided proper oversight of close to a billion dollars in proposed projects. “State officials attacked us again, saying the stories weren’t accurate — and yet they couldn’t point to any mistakes,” Galloway said.

In 2015, Digger reported that the Securities and Exchange Commission was investigating Jay Peak developers and that the state of Vermont had raised questions about another EB-5 program, a proposed biomedical manufacturing plant.

A year later, the SEC charged both Stenger and Quiros with 52 counts of securities fraud and with misusing $200 million in immigrant investor funds. In all, the developers were charged with defrauding 836 investors from 74 countries. Quiros settled with the SEC for $84 million in January 2018; Stenger was hit with a penalty of $75,000 for his role in the fraud.

Digger was vindicated for stories that had gotten a skeptical and dismissive reception in the state’s newspapers. “Suddenly I looked like someone with a crystal ball,” Galloway said. “People were awestruck that we were right.”

Curtis Koren, the chair of Digger’s board, credits Galloway’s doggedness. “She reported on that story for two years before the SEC brought its charges. People were saying it’s not a story, it’ll be good for the economy, bring all these jobs, it’s not a problem. And she kept going and going and came out with a really important story for Vermont.”

Digger has published more than 250 stories on this subject.

“EB-5 put Digger in the minds of people,” said board member Carin Pratt. “It put them on the investigative map and their presence really grew after that.”

It was a game changer for the site. The SEC charges brought heightened credibility. Stories won major reporting awards and Digger’s work was mentioned by The New York Times, PBS NewsHour, BBC’s The World, The Boston Globe and others. ProPublica produced a podcast on the backstory.

“The result is people really look to us to investigate all kinds of things,” Galloway said.

And investigate they have.

Digger has since broken stories about allegations of fraud by a town clerk in Coventry, a federal investigation into Jane Sanders’ (wife of Sen. Bernie Sanders) tenure as president of Burlington College, sexual harassment and fraud at an opiate treatment center, questionable expenditures by the state’s biggest hospital, and widespread environmental damage from a Teflon plant in Bennington.

Digger’s original focus — on investigative reporting and daily statehouse coverage — remained at its core. But over time, after watching the continued decline in local reporting by the state’s daily newspapers and the Associated Press, Galloway was convinced Digger had an opportunity and responsibility to expand, when the time was right.

By 2013, Digger had found itself on more solid financial footing, and Galloway had more confidence to invest in news reporting. She created new beats, with an emphasis on Vermont’s biggest policy topics. Those include the environment, as solar and wind energy are key issues, and health care, since the legislature was considering a single-payer bill, which ultimately failed.

From 2014 to 2016, Digger began expanding regionally. With a daily presence in the legislature, Galloway noticed important issues arising out of communities across the state were going uncovered. For example, Vermont Yankee, the nuclear power plant in the southern town of Vernon, was being decommissioned. Local reporters weren’t capturing the context of that story, and certainly weren’t making it relevant for readers elsewhere in the state.

In Rutland and Chittenden counties, Digger has dedicated reporters. And the site has formed partnerships to expand further, backed in part by a grant from the Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation to fund a southern Vermont presence. In Brattleboro, Digger splits the cost of a reporter with the Reformer, the local newspaper. Stories appear in both outlets. And in Bennington, Digger helps cover the costs of a reporter for another local paper, the Banner.

Digger now has reporters based in four counties with aspirations to do the same in all 14 counties.

Strategy: Expand through collaboration

Where possible, consider hiring interns and freelancers first, then hire full-time reporters when the budget allows. Most importantly, consider partnerships at every turn to help expand your capacity and capabilities at lower cost. Betternews.org has a primer on the value of partnerships. CollaborativeJournalism.org offers an extensive study of the ins and outs of editorial collaborations of all types.

In January 2017, after extensively covering Bernie Sanders’ failed presidential campaign, the site hired a full-time reporter in Washington, D.C., Elizabeth Hewitt, who covers the state’s congressional delegation and national policies that affect Vermont. Digger believes it is the only news outlet in Vermont that has ever maintained a D.C.-based reporter, and the only New England outlet besides The Boston Globe to have a dedicated D.C. bureau chief.

Digger now publishes eight to 12 stories per day.

An often-overlooked ingredient in the success of any enterprise is the makeup and effectiveness of its board. Digger’s board of trustees — still technically the Vermont Journalism Trust — is 14 strong, with a healthy mix of backgrounds in journalism, finance, fundraising, public relations, and philanthropy.

“People with expertise in various fields and standing in the state tend to actually want to be involved, and we try to make sure that happens,” said Koren, the board chair. “Why have a bunch of movers and shakers signed up for the board if they’re not given the opportunity to move and shake?”

The board contributes financially in a big way; in 2017 its members collectively gave just over $100,000, or 8 percent of the total operating budget. Koren said some board members are independently wealthy, but most are not. “It just shows a commitment to the cause. They all admire [Digger]. They’re all in.”

Galloway and Koren make a big deal about financial contributions by the board: They call these gifts out separately in their budget and actively solicit via the board’s development committee during fund drives. They remind members at every meeting about the importance of 100 percent giving from the board, which is often expected or required by foundations and other donors. And they expect all 14 members to actively pitch potential donors in their respective networks and facilitate contacts for the Digger development staff.

Perhaps more impressive than financial contributions are the other ways in which the board gets involved.

Board members seem to embrace the role of evangelizing on behalf of the brand to friends, co-workers, and even strangers. When Carin Pratt, a board member and former executive producer of CBS’ “Face the Nation,” meets someone who doesn’t get the daily Digger email, she writes down their email address and sends a note to the staff to sign them up. Board members also write thank-you notes to contributors and solicitation notes to potential donors, set up meetings with the community and staff, and throw dinner parties designed to spread the word.

Galloway says the board has been key to Digger’s success. She relies heavily on the board for advice and has worked hard to cultivate relationships that make seeking guidance easy and productive.

“It’s hard to be a leader,” Pratt said. “It’s hard to be that one person who’s making editorial decisions but also strategic decisions about the future of the organization.”

Strategy: Get the most out of your board

A nonprofit news board is always responsible for the financial stability of the institution. Beyond that, types of boards vary widely but they’re often by nature governance boards (making strategic decisions), advisory boards (providing strategic guidance to the staff), or fundraising boards (the chief development arm of the institution.) In Digger’s case, the board serves all of these functions. Your board’s role may be governed by its charter, but it’s worth thinking about what you, as a staff, want or need from your board. What expectations do you have for your board and its members? Is it the right size/makeup to help you reach your goals? Do you have the right diversity? How can they help you maximize your reach, your journalism or your revenue?

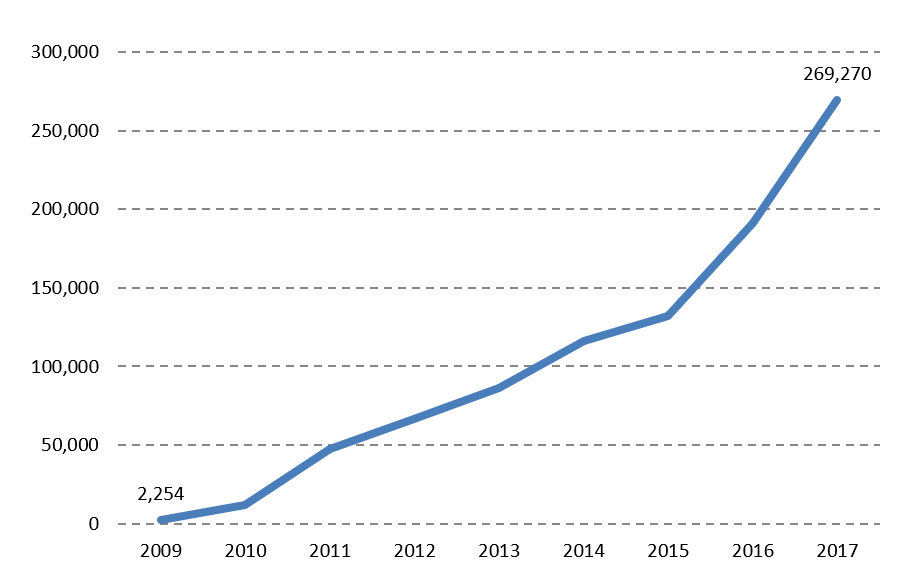

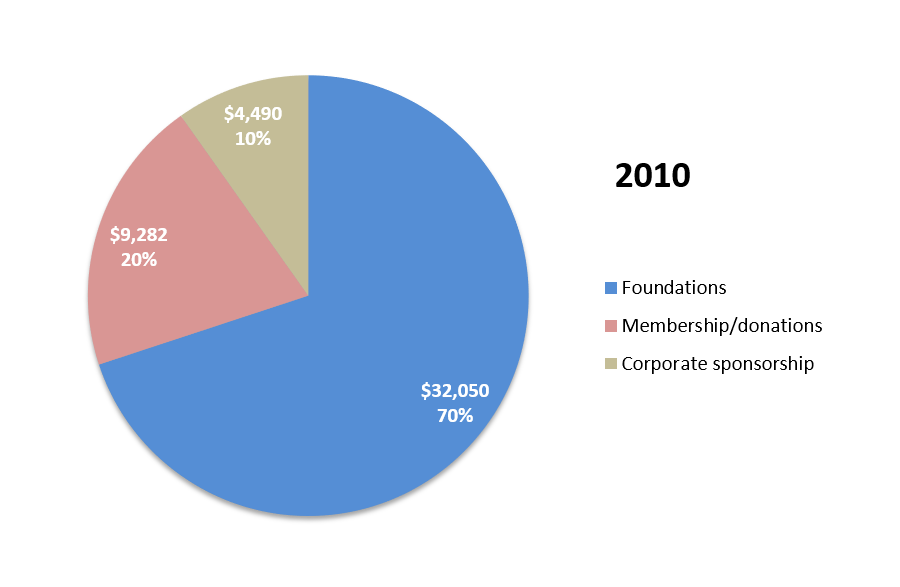

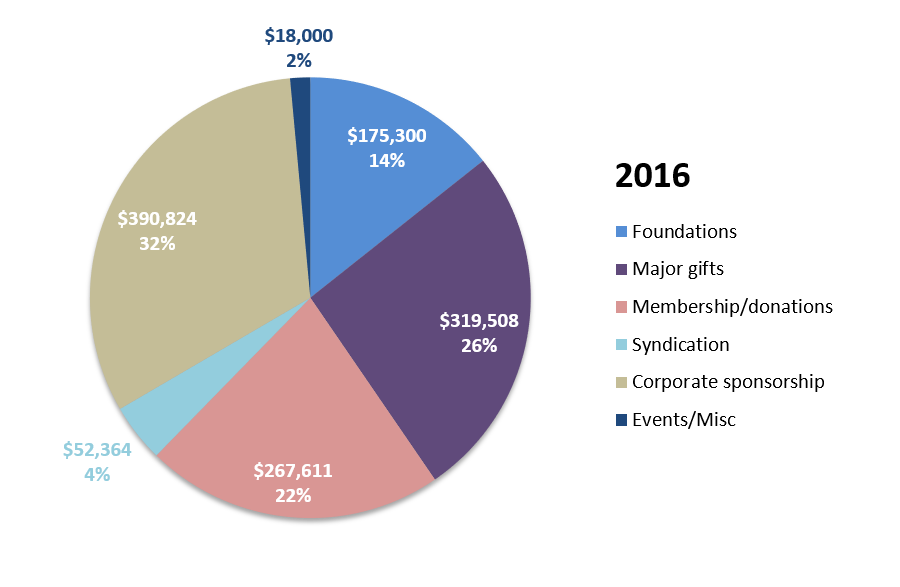

Galloway, from Day One, has been intensely focused on making money to support Digger’s existence. Every major line of revenue has grown (typically double-digit percentage growth) year-over-year. Membership has grown from $10,000 in 2010 to nearly $330,000 in 2017. Corporate sponsorship, a tough nut to crack for many local news organizations, nonprofit or otherwise, was just short of $400,000 in 2017.

Galloway says that each time Digger gets to a strong base level of support and mastery in any area, it is time to tackle something new. She worries about stretching herself and her staff too thin, of course, but errs on the side of experimenting with new platforms, new revenue ideas, and long-shot bets. “You can never stop trying to grow,” she said.

Events are a good example. In its early years, Digger did about one live event a year. In 2016, it jumped to four events on its own and co-produced two others with partners. In 2017, the list expanded to 16 news events and casual gatherings, which have been well received by readers and supporters, although they remain a monetization challenge. “They’re a time suck,” Galloway said, but they’re worth it as a tool for connecting readers to the Digger brand and developing loyalty. More work needs to be done to find event sponsors, and there’s more to test around paid, ticketed events.

Over the last couple years, the Digger team has greatly expanded its products and services. Among them:

Digger also has plans to start posting classifieds — a job board, obituaries, legals — as a revenue and audience-building experiment. Galloway said readers were asking for these kinds of services and felt it was an opportunity to provide a service for people who stopped reading the local newspaper or are dissatisfied with Craigslist.

“You have to constantly think of new ways to serve people,” she said. “Even with businesses. How do we help them connect with people and improve their business prospects?”

In 2016, after the recognition that came from Digger’s EB-5 coverage, Galloway was introduced by board members to Lyman Orton, whose family owns The Vermont Country Store. After a couple of meetings it became clear to Galloway that Orton appreciated Digger and wanted to be part of something transformative.

“He liked us and what we were doing,” she said. “But he’s also a business guy and very practical. He said, ‘I don’t want to do it by myself.’ He saw an opportunity to leverage his money and get other people involved.”

The result: A multiyear, multimillion-dollar “growth fund.” Unlike an endowment, which theoretically lasts in perpetuity but throws off only a fraction of the total in cash (usually 5 or 6 percent, depending on the investments), Orton wanted Digger to spend money now to fuel its growth.

Strategy: Diversify

Don’t buy into the notion that there’s an ideal number of revenue streams for news organizations. “There’s no limit on ideas here,” Galloway said. “If you told me tomorrow that there was some idea I’m missing, I’d latch onto it. Then I’d think, ‘what’s the ROI?’” The reality is that no two markets are the same; what works in one place for one site may or may not work for you. Be wary of silver bullets (they don’t exist) and instead constantly and continually experiment and test ideas to generate revenue. In other words “fail fast, fail cheap.” BetterNews.org offers a primer on the importance of revenue diversification.

Orton and his wife, Janice Izzi, gave $1 million to help catalyze an investment from other wealthy philanthropists across the state. On a $5 million goal, Digger is up to almost $2 million (about $750,000 in hand, and an additional $1.2 million in pledges).

The growth fund’s objective is to double readership, revenue, and impact in five years. So, by 2022, Digger expects to generate nearly $3 million in annual operating revenue. Essentially the pitch was: “give us the funds to spend right now, to spend on business, technology, and reporting, so that funding will be sustainable in year six.”

The plan, underway now, includes:

“When we first talked to (Orton) about getting $1 million per year for five years, (Galloway) and I said, ‘We can’t spend that much money, really, could we?’” But it gave us the confidence to go ahead and do it, to grow fast and smart,” Koren said.

Strategy: Never stop looking for capital

Most nonprofit news sites have launched without adequate capital to build viable long-term businesses. Digger was no exception. Although its approach to organic, pay-as-you-go growth has worked, the odds of success are much greater with runway in the form of pre-launch funding, a la Mississippi Today, a major endowment, or in Digger’s case, a large infusion of cash to invest in infrastructure and growth. You may not have a Lyman Orton in your neck of the woods, but always keep an eye open for someone (or many someones) who may want to make a bold bet on your future.

When you hear from peers at INN events or read success stories in the journalism trade press do you think, “That would never work here?” or do you think, “How can I apply some part of that to my market?”

There’s really no secret sauce to Digger’s success. But certainly one of its strengths is the ability of the institution and its leaders to pay attention to successes and failures elsewhere and apply them locally. Innovation, after all, doesn’t just mean new. It can also mean new here.

“I would go to these conferences and always try to learn what others are doing and adapt to our purposes,” Galloway said. She recalled learning about the Knight-funded membership initiative by MinnPost and Voice of San Diego. “We didn’t have the patience to wait for the results of that, so we just built our own donate page,” she said. “We’re idea crazy. I like to look at what other people are doing and then adapt them to us. For example, what if we offered a new afternoon product as a perk to people who are paying more than $5 a month in membership? How hard is it to do this? We don’t have the easiest system on the back-end to make it possible. So maybe we’ll hack it.”

Galloway credits her web developer, Stacey Peters, with coming up with revenue ideas and tech solutions that augment the news.

It may sound cliché, but embrace the concept of “fail fast, fail cheap.”

In 2011, Galloway landed a $25,000 grant to build a customized Facebook platform for readers to submit news tips. “It was a very expensive dumb idea,” Galloway said. “It would’ve taken $1 million to do it right. It broke incessantly. The developer practically had a breakdown on it.”

Instead of sulking — or possibly after sulking — Galloway kept the idea but simplified it to a simple form at the bottom of stories. “People use it all the time,” she said, estimating 6-10 readers a week reach the newsroom through the form.

Digger subsequently built forms for submitting documents and another for corrections.

“I went to a conference and Craig Newmark was on a panel complaining about how news organizations don’t respond to corrections very quickly,” Galloway said. “There should be an easy way for readers to suggest them. Sometimes people don’t want to identify themselves by sending an email — and that’s OK. I took that to heart and went to our web developer and we put it in place right away.”

Email newsletters are one of the most important tools in your publishing toolkit. Compared with distributed content (like social and search), email is perhaps the most important path to building relationships with audiences outside your own site. You control virtually the entire experience: the tone, timing, content, design. You have access to powerful analytics and can alter the product easily based on them. And email will likely be your most important channel for soliciting memberships/donations. Getting good at both acquiring new emails and deepening engagement with folks you have is critically important.

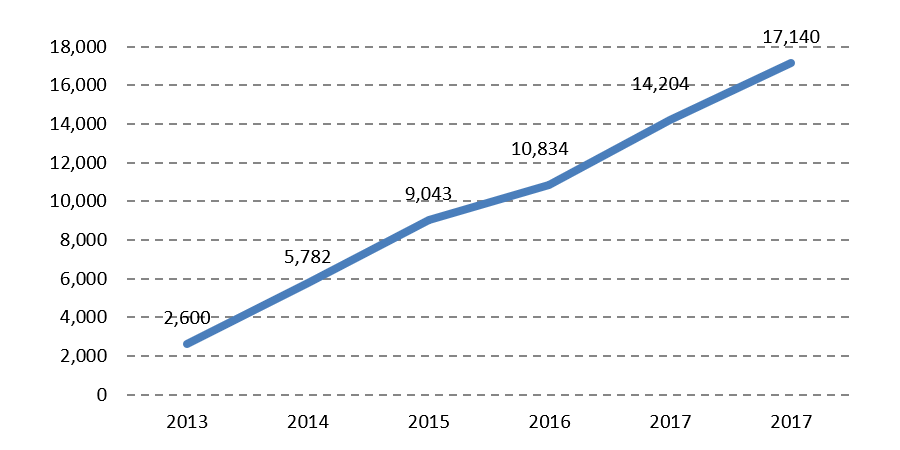

Digger has seen double-digit percentage growth in email subscribers every year since 2013. Why?

Digger currently sends a daily news summary Monday through Saturday and a weekly summary on Sundays. In 2018, the site launched breaking news bulletins and topic-based weekly newsletters.

It may be less sexy than social, but traffic from Google remains an important lever for reach, perhaps more so after changes to Facebook’s News Feed.

Digger performs well in search referral traffic. Among the reasons:

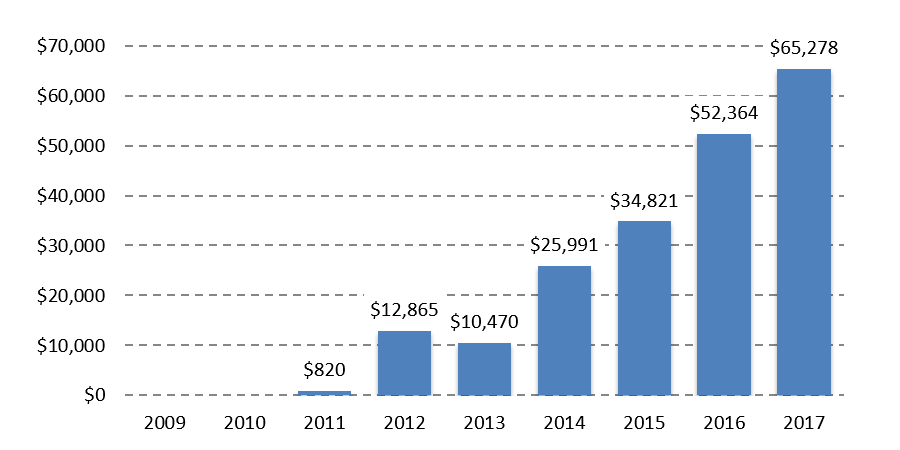

Many nonprofit news outlets distribute content to newspapers and broadcast outlets — for both altruistic/mission and reach/discovery reasons. Few have made paid syndication a meaningful revenue line. Creating complex long-term agreements runs the risk of cash-strapped legacy news partners saying no, even with obvious benefits.

Digger has a simpler approach: Low-cost, flat-rate pricing — usually $40-$60 per week, depending on the outlet — for access to everything Digger produces. This tends to be more palatable than $2,000-$3,000 annual contracts. Digger also offers à la carte options (usually $50 for a story or $25 for a photo). Phayvanh Luekhamhan, one of the unsung heroes of Digger’s business operation, keeps a simple spreadsheet and invoices its 15 or so partners.

Syndication revenue in 2017 will top $60,000 — enough to cover a reporter or two.

Since 2013, the Digger staff has hosted an annual “open house,” inviting readers and members to mingle with lawmakers, politicos, and lobbyists.

“Part of what makes Digger cool,” Koren said, “is that we have readers across the political spectrum.” The organization’s audience research suggests half self-identify as conservative/Republican, and the other half liberal/Democrat. “Missing in both the national conversation and the local conversation is that it’s OK to disagree. That’s what makes democracy great, and we love to get people together to eat and talk and try to understand others’ perspective.” The open house in January 2018 had about 200 attendees.

Are you helping your audiences connect with you — and each other — beyond news events? Consider happy hours, trivia nights, debate/election “watch parties,” newsroom tours, and other ways to give readers a peek beyond the curtain, and build long-term relationships in the process.

Your nonprofit news organization may have a dedicated sponsorship sales lead, a development director who writes grant requests, or a board member who’s responsible for major individual gifts. But, chances are, before a big check is written, big supporters want to talk with the editor.

Embrace that opportunity.

At Digger, Galloway started off feeling “nobody knew who the heck I was,” but she now plays the celebrity role with underwriters and businesses, helping salespeople get in the door. Businesses “really can’t say no, partly because I think they’re all a little afraid of me. But they know who I am and they want to hear from me.”

Murray-Clasen, Digger’s director of underwriting, says having Galloway join sales calls helps hone the pitch and close deals.

“Going out together (with the editor or executive director) helps them understand what’s working, what’s not. Then we go back and dissect it, figure out where the weaknesses are. Anne did that and still does. In the early days, she went out just to listen and empathize with me.”

Galloway was once uncomfortable with fundraising, worried about compromising her journalist integrity. But, like anything, a little practice goes a long way. “If the conversation veers into someone trying to influence us, I just say that’s not ethical. I set boundaries. People get it. They get there are rules. You just have to explain what they are.”

When Galloway was a high school student, selling tennis shoes after school and in the summer, she learned a lot about sales. “I just tried to figure out what people wanted,” she said. “It’s similar to reporting — you try to understand them and their interests, empathize with them, and have respect for them.”

The same theory applies to sponsors, foundations, members, and major donors: No single message will appeal to everyone.

“You need to adopt your pitch based on who you’re selling to,” Murray-Clasen said. ‘I’ll never not sell the mission (to potential sponsors), but I may slant it depending on the person. If they’re retail-oriented, I’m going to talk numbers. Make sure they understand they’re not just getting the impressions but also doing something good for Vermont and for democracy.”

For small businesses, Murray-Clasen emphasizes buying local: “You want consumers to buy your local stuff? You need to buy local, too.”

Nonprofit news sites are always looking for ways to best determine and track impact. There are tools like Chalkbeat’s Measures of Our Reporting Influence and The Center for Investigative Reporting’s Impact Tracker that help with the latter. Digger, for its part, highlights the most significant stories that have had a qualitative impact in special sections on the site, via links just below the masthead and in special features at the bottom of the front page. Digger features high-impact stories in its annual report.

Digger also captures reader testimonials in an interesting and replicable way: As part of the membership sign-up process, new supporters are prompted to write a few words about why they chose to become members. Responses are curated and put in a table that’s then coded into the site and deployed during fundraising drives.

One of the major problems facing small nonprofit news sites (and, really, all small businesses) is fatigue. How do you keep your spirit in the face of exhaustion? How do you keep your team’s energy up, when it can be a struggle to keep the lights on? How do you prioritize the thousands of tasks in front of you? Here are some words of wisdom from the Digger staff:

About the Author: Tim Griggs is an independent consultant and adviser to media companies, foundations and others on revenue growth, audience development, newsroom transformation, and digital strategy. He’s the former publisher of the Texas Tribune, executive director of revenue products at The New York Times, and editor of the Wilmington (N.C.) Star-News. He is a former board member of the Institute for Nonprofit News (where he served with Galloway) and he has done some paid consulting work for VTDigger on sustainability and best practices.

Editing was provided by Howard Goldberg.

About the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy: The Shorenstein Center is a research center based at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, with a mission to study and analyze the power of media and technology and its impact on governance, public policy, and politics. Research, courses, fellowships, public events, and engagement with students, scholars, and journalists form the core of the Center. For more information, visit shorensteincenter.org.

The Institute for Nonprofit News support a network of independent, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more about INN.

Back to top