Lessons from Startups: 10 Founders of Local Nonprofit News Outlets Share Their Motivations, Struggles

By Katrina Janco for the Institute for Nonprofit News

July 15, 2022

Local, nonprofit news outlets are surging in number.

INN’s Index data show well over half — 55% — of nonprofit news launches since 2017 are locally focused organizations, and the growth in local launches has become more pronounced in the past couple of years. In 2020, 57% of new launches were local; in 2021, this number rose to 65%. Based on early data we’re seeing from 2022, we expect this trend to continue.

INN wanted to better understand the drivers behind this local, startup wave, and how INN can further support nonprofit newsroom founders. So, we asked 10 local, nonprofit news founders to recount what motivated them in the beginning, what resources and training helped them along the way, and what they wished they had known sooner.

Jump here to see the full list of outlets included in this story.

Use these resources: INN offers several resources for startup nonprofit news outlets and aspiring founders, including a Startup Guide and peer communities for startups. See here for a full list of INN’s news startup resources.

Motivations for Starting a Newsroom

A universal theme among founders was saving and bolstering local news.

According to a 2020 report by UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media, about 1 in 4 newspapers have vanished in recent years, with almost 2,100 papers lost since 2004. Report for America estimates that there were seven daily newspaper journalists per 100,000 people across the United States in 2019, down from 22 reporters per 100,000 people in 1990.

In Arizona, however, the situation may be even worse. There are just 3 reporters per 100,000 people, according to a media ecosystem study done by Arizona Luminaria. A Tucson native, Arizona Luminaria co-founder Irene McKisson could see the news gaps and how many fewer journalists there were in the state. While fundraising, McKisson has run into people who see its tangible effects. “We see it really clearly from people who are like, ‘yes, I can see how this disinvestment in journalists has led to issues that I have as a reader, as a citizen, that I have trouble getting this information,’” she said.

McKisson isn’t alone. In numerous cases, people in the community who knew the founders asked them to do something. After DNAinfo Chicago was abruptly shuttered, Stephanie Lulay and her fellow laid-off editors began hearing from readers who were very upset by the decision. “They would tell us, ‘why didn’t you guys just ask me to pay for this? I would have paid for it if it was going out of business,’” Lulay said. Hearing from so many readers motivated Lulay and her co-workers to create a neighborhood-based outlet, which later became Block Club Chicago.

For Robert Moore, the call to action came from community leaders who were concerned about the state of local news in El Paso. He eventually launched El Paso Matters with the help of El Paso Community Foundation, which had previously launched a nonprofit newsroom that never truly got off the ground.

Inseparable from the decline of local news are the constant layoffs throughout recent decades in journalism. According to an analysis by the Pew Research Center, newsroom employment fell 26% since 2008, with newspaper publishers facing the most jobs lost.

For INN board member representative Kelsey Ryan of the Kansas City Beacon, she knew she didn’t want to work for another newspaper chain by the end of the first day after she was laid off from The Kansas City Star. “The business problems weren’t going away. It’d just be like taking a lifeboat to another sinking ship. So I basically was like, ‘I’m going to build my own ship,’” she said of her inspiration to start The Kansas City Beacon.

Outlets were founded within the context of the respective local media ecosystem to cover what traditional newsrooms don’t. “We’re not here to compete with the daily newspaper. We are here to supplement,” Kestin said. “Our only goal is to fill the void of what’s missing in journalism in Asheville, and do the stories that take a long time, that are hard to do, that the existing media here can’t do or don’t have the time to do.”

When Serena Daniels began focusing on food and identity as a freelance journalist in Detroit, stories about communities of color and food were considered an afterthought, and only noteworthy during some holidays. Frustrated with traditional food writing while growing a readership in the community, she decided to start Tostada Magazine. “It was the right moment to say, ‘You know what, I think I can just as easily do this on my own as I can pitching to other publications.’ In that way, I would have ownership of my stories as well, and I wouldn’t have to ask for permission any longer to publish the kinds of stories I really cared about,” she said.

While many nonprofit newsroom founders worked in journalism prior to starting their outlets, some did not. An urban planner for years, Danielle Bergstrom started Fresnoland as a think tank to do original research on local policy issues, which led to partnering with storytellers in the community to explain the issues. It was only when a mentor pointed out that the ethos of the project was public service journalism that she realized she was doing journalism.

“I really didn’t think to go to journalism, because a lot of traditional journalism has been who, what, when, where, why, but not so much pulling back and saying, ‘Why is this happening, what’s the historical context on this issue, and what can you do about it?’” Bergstrom said. She was initially hesitant to apply the label to herself and her work, not wanting to purport to be something she believed she wasn’t. However, she met with The Fresno Bee to publish her research as reported stories, and together they created an ongoing collaboration called the Fresnoland Lab.

Others, like Cicero Independiente’s Irene Romulo, started down the journalism path after seeing the media’s shortcomings. Prior to co-founding Cicero Independiente, Romulo worked as an immigration organizer. She saw the media not meeting the informational needs of immigrant communities, and focusing solely on immigrants’ trauma. Looking to start a journalism project for Cicero’s immigrant community, Romulo applied to and received a fellowship with Chicago-based nonprofit newsroom and INN member City Bureau. During the fellowship, she met April Alonso and Ankur Singh, and they combined their efforts to form Cicero Independiente.

Why Adopt the Nonprofit Model?

For some founders, going nonprofit was a core motivation for starting a news outlet, or simply a no-brainer. While working at the Las Vegas Review-Journal, Ramona Giwargis was inspired by The Nevada Independent, a member of INN, and was determined to bring that model to San José, her hometown. “If it works in Nevada, a rural state, why can’t it work in San José, the heart of so much wealth?” she recalled thinking as she brainstormed what would become San José Spotlight. Other founders jumped into creating their news organization, knowing they wanted their content to be free, but more intentionally embracing the nonprofit model only later.

Other founders took time to study various business models, and talked with others in journalism and elsewhere. Regardless of how long the decision took, founders had similar reasons for going nonprofit.

They wanted their content to be a public good and free for everyone, which was particularly relevant in low-wealth communities. Going nonprofit was seen as a way to gain readers’ trust. As Lulay of Block Club Chicago put it, “When people gave to us, we wanted them to know that no one was getting rich off of their contribution, and that it really was going back into producing quality journalism in their neighborhoods. By being a nonprofit, that’s the easiest way to communicate that.”

Another motivation to start a nonprofit newsroom was the ability to have multiple revenue streams, including foundations and major donors, as explained in these INN Guides. “What I realized pretty early on is that you have to make revenue regardless of whether or not you’re a for-profit or a nonprofit,” Ryan said. But by becoming a nonprofit, newsrooms could access grant money faster, which tipped the scale for Ryan to go nonprofit. Some, such as McKisson and her Arizona Luminaria co-founders, had experience applying for grants, and knew it could be available to support their journalism. This was a priority in low-wealth communities.

Beyond wanting multiple revenue streams, founders sought to avoid being dependent on advertising, and the frequent layoffs and other bad incentives that come with the model. As an editor at El Paso Times, Moore was forced to lay off more than 40 people from 2007 to 2017, before he resigned after being requested to reduce payroll again. Once he started to create El Paso Matters, the decision to go nonprofit was obvious. “I just did not see a for-profit path that made any sense at all,” he said.

Although Romulo did not have a journalism background, she and her Cicero Independiente co-founders had similar reasons for choosing the nonprofit route, seeing it as the best way to prioritize employees’ wellbeing and have more community input into their journalism. This decision was aided by research done in collaboration with a legal clinic from the University of Illinois Chicago’s School of Law.

What Resources and Training Were Available?

For those with a journalism background serving as their primary resource for starting a newsroom, freelance experience was especially helpful because it requires essentially running a business. They did not necessarily have a lot of opportunities to try out different newsroom functions at their previous jobs, but at the Arizona Daily Star, McKisson and her co-founders had learned new skills, including selling digital advertising, experimenting with sponsored content, producing live events, and launching a membership program. Having a team with complementary skills across the newsroom helped while starting Arizona Luminaria. The few who had business experience outside of journalism found this background to be beneficial. Those with multiple founders benefited from having a team of people working together to start a news outlet.

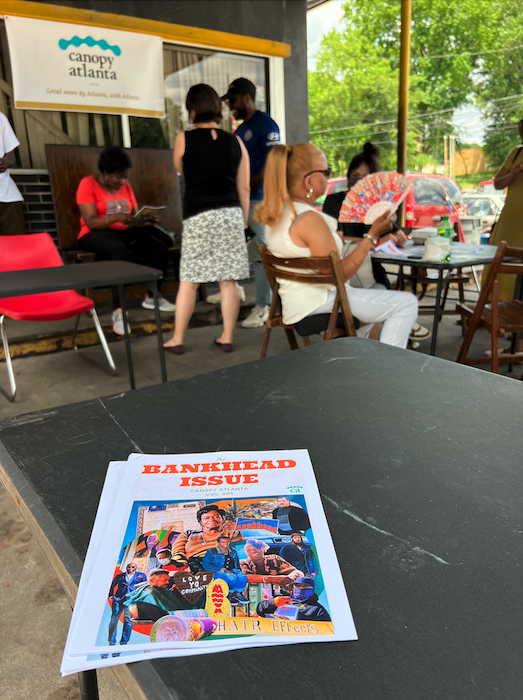

For those who did not start in journalism, their backgrounds helped them while beginning and growing a nonprofit newsroom. Bergstrom’s past in urban planning, and the practice of turning lots of data and its findings into articles and policy suggestions helped her succeed in data journalism, while Josh Barousse’s experience in politics guided him as he led fundraising efforts for San José Spotlight. Canopy Atlanta had six co-founders, and the variety of experiences among them has been instrumental in the publication’s success.

Local communities were vital for growing these newsrooms, from funding from local foundations and readers, to early community sessions and conversations that formed their editorial lenses. Most newsroom founders did outreach to learn and better understand what the community needed and wanted from local news, although some plans fell through because of the pandemic. This outreach was particularly important, as residents had different priorities than what founders expected, no matter how connected founders were to the community. Some took business seminars in their community, and other non-journalism specific entrepreneurial opportunities, to better learn how to run their newsrooms. Taking a class with the Build Institute helped Daniels with business basics that allowed her to apply to grants from the Detroit Media Engagement Fund, and Allied Media Projects to become Tostada Magazine’s fiscal sponsor.

The Google News Initiative, INN and its NewsMatch initiative, LION Publishers, and the Meta Journalism Project were the most commonly cited as critical resources to launching and sustaining the newsrooms.

Other helpful opportunities and organizations noted by founders include the ONA Women’s Leadership Accelerator, fellowships with First Draft News, the American Journalism Project, Report for America, the Lenfest Institute’s News Philanthropy Network, the Media Transformation Challenge hosted by the Poynter Institute, the Solutions Journalism Network, Lawyers for Reporters, the The Texas Tribune’s RevLab training program, and the Listening Post Collective.

Struggles and Wish Lists

The biggest struggles for nonprofit newsroom founders were challenges related to jumping into something they had never done before, and adapting to changes in the journalism industry generally, specifically around social media and audience engagement. The latter was particularly true for older founders. The pandemic was challenging in many ways but emergency grants helped as the founders rose to the occasion by focusing on service journalism and providing accurate information on COVID-19.

Founders also stressed the need for a toolkit, roadmap, or checklist of tasks that must be done before launching, and what kind of expectations should be had. INN provides these resources, including a Startup Guide.

Finances: seed money, paid fellowships, and sustainability

When asked about what nonprofit newsrooms need, Lulay put it bluntly: “The answer is very simple — it’s money. If we are going to build nonprofit newsrooms that serve marginalized audiences, really new next-generation nonprofit newsrooms run by journalists, those journalists need the money to do it.” Lulay also stressed the need for it to come at the right time. “You need to get this newsroom off the ground and up and running enough to be able to hire staff before you burn out. That’s the clock that founders are up against.”

Founders discussed the need for support regarding finances throughout the process, from seed money and fellowships, to creating a sustainable financial model and fundraising. INN has a Network Philanthropy Center, News Giving Roadmap and Major Gifts Coaching Program, among other fundraising resources.

Seed money is particularly important, both for logistics and morale, even if it isn’t a lot. When Canopy Atlanta received its initial $50,000 grant from MailChimp, co-founder Floyd Hall recalled that it gave the co-founders more confidence to solicit other donors. For Bergstrom, a startup grant from a local community foundation gave her a space to experiment. Even though she ended up pivoting from a think tank to a journalism outlet, she was able to leverage that initial research when making her case to later funders.

Many of the newsroom founders interviewed for this report worked without pay for an extended time while starting their newsrooms, a privilege most people cannot afford. Romulo was able to build Cicero Independiente while she was a Voqal fellow, and says more paid opportunities are needed for potential founders trying to learn more about nonprofit journalism.

Founders raised concerns about how grant funding is limited, unavailable in some communities, and favors newsrooms that are already well-established over vulnerable startups; San José Spotlight had only cracked foundational grant opportunities in the last 12 to 18 months, not in the runup to its launch in January 2019. Chasing foundation support can also affect news organizations’ priorities and divert them from their initial vision.

There are also concerns among founders that nonprofit newsrooms in smaller, low-income, and/or rural communities are not given enough attention or funding. “I worry about how we parlay this excitement about what’s happening in our major metropolitan areas [and] how do we turn it into that same excitement for news in other places,” Lulay said.

Building and serving diverse audiences

While all the founders had connections to the communities they cover, audience development has been difficult. This is particularly relevant in newsrooms that cover more than one community, and with older founders who did not have to worry about social media at the start of their careers. Looking back on what he would have done differently, Moore said his first hire would have been an audience development director rather than a journalist. “The old movie line, build it and they will come, just does not work in the journalism realm,” Moore said. One successful strategy has been for founders to start a newsletter as a way to build an audience before launching a website.

Founders frequently pointed out the need for more resources on producing content in different languages. According to the most recent estimate from the American Community Survey, 21.5% of Americans speak a language other than English at home. Additionally, online platforms like Facebook and YouTube have allowed mis- and disinformation not in English to freely spread, making the need for multilingual journalism even more prudent as the number of non-English speakers in America is expected to continue growing. Content that helps fill information gaps is good for engagement; for Tostada Magazine some of the most-read content in its history was English-language content translated into Spanish by a volunteer who reached out and offered help to Daniels after seeing her work.

Part of the problem is diversifying the applicant pool, entangled with the lack of funding for diversity initiatives in media. San José Spotlight has made a deliberate effort to diversify its newsroom. It has devoted resources to broadening recruitment using LinkedIn and job listings on journalism association websites, hiring interpreters for live events, and upgrading translation tools on the website. If funding were available for these initiatives, other newsrooms may do more to diversify their newsrooms and their content, said Giwargis and Barousse.

Newsrooms have tried addressing this issue by translating their English-language content into other languages. This strategy alone, however, cannot be the answer. Translations are expensive, difficult, and time-consuming. Solely translating English content into another language ignores differences in culture and informational needs between communities. There is also the potential for newsroom equity issues, if newsrooms expect bilingual reporters to also be translators, while their monolingual peers don’t have that same responsibility.

One strategy has been to partner with media organizations that already have established relationships with the community. El Paso Matters is looking to collaborate with the local Univision affiliate on voter guides. Besides translations, Fresnoland’s reporters, who are bilingual, speak about their reporting on Radio Bilingüe, a Spanish-language public radio station based in Fresno where many farmworkers get their news. In addition, Fresnoland is currently working on identifying local organizations connected to Fresno’s Punjabi and Hmong communities to partner with. “We can develop a product on our website that we think is going to serve those communities, but honestly, go where people already are,” Bergstrom said.

Support and shared resources on how to run a nonprofit newsroom

Founders often ran into issues with the administrative day-to-day operations. What does a freelancer contract or a budget look like? How does a nonprofit newsroom develop workplace HR policies, payroll, or pick a board of directors? What organization provides the best liability insurance? Founders emphasized the need for shared resources in this area of running a nonprofit newsroom, and specific resources by state, as employment laws differ across the country. There is a particular lack of resources for workplaces that aspire to have more collaborative and less hierarchical leadership structures, or worker-led organizations. There was also a need for more shared resources for fundraising, such as on creating a compelling pitch deck, writing a case for support, and pitches to donors.

There was also a need for more cohorts and being able to talk to peer nonprofit newsrooms and share best practices, such as by region or when they launched. This is particularly relevant for those who were not originally in journalism; Bergstrom labeled her lack of a journalism network as the worst part of not having a journalism background when starting Fresnoland. “I don’t have friends from j-school I could call up and be like, ‘hey, I’m dealing with XYZ issue.’ I could call my friends from planning school and they’ll be like, ‘I think I have a friend that works at The New York Times if you want to talk to them,’” she said of the struggle.

Use these resources: INN offers several resources for startup nonprofit news outlets and aspiring founders, including a Startup Guide and peer communities for startups. See here for a full list of INN’s news startup resources.

Conclusion

The main takeaways from this report are as follows:

- The failures of the traditional ad-based model of journalism and a desire to serve the informational needs of their communities are the key motivators for founders to start nonprofit newsrooms, regardless of whether or not they were initially journalists.

- Local communities are crucial to the success of local nonprofit newsrooms, from informing editorial strategy, community trust, local foundation and donor support, and reader dollars. Future nonprofit newsroom founders must know and engage with their communities and their informational needs prior to starting a newsroom, and invest in audience development.

- Journalists need more fundraising, nonprofit management, and operations training, support, and resources, and ways to build a sustainable newsroom that meets the informational needs of the entire community.

We gratefully acknowledge these members for providing interviews for this report:

Arizona Luminaria was founded in 2021 by Irene McKisson, Becky Pallack, and Dianna Náñez to provide Arizonians with local news and community-centered journalism.

Asheville Watchdog was founded in 2020 in North Carolina by Bob Gremillion and Sally Kestin to provide the community with investigative reporting in the public interest.

Block Club Chicago was founded in 2018 by Stephanie Lulay, Jen Sabella, and Shamus Toomey to report on Chicago’s diverse neighborhoods.

Canopy Atlanta was founded in 2020 by Max Blau, Floyd Hall, Sonam Vashi, Kamille Whittaker, Mariann Martin, and Mike Jordan to create community-powered journalism in Atlanta.

Cicero Independiente was founded in 2019 by Irene Romulo, April Alonso, and Ankur Singh to serve the immigrant community of Cicero, Illinois.

El Paso Matters was founded in 2019 by Robert Moore to serve the El Paso and Paso del Norte region in Texas.

Fresnoland was initially founded as a think tank in 2018 by Danielle Bergstrom, but since 2020 has been published by the Fresno Bee as the Fresnoland Lab, focusing on the issues closest to the residents of Fresno, California.

The Kansas City Beacon was founded in 2020 by Kelsey Ryan to provide Missourians and Kansans with in-depth local news.

San José Spotlight was founded in 2019 by Ramona Giwargis and Josh Barousse to serve the residents of San José, California, with in-depth political and business reporting.

Tostada Magazine was founded in 2017 by Serena Maria Daniels to provide inclusive and diverse food journalism for Detroit.