Funding from Foundations

In the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors, there is growing attention to questions around equity in funding. Recent research has documented disparities in funding between BIPOC-led and white-led organizations in the nonprofit sector, as well as inequities in accessing philanthropic support experienced by BIPOC-founded news outlets.27 Against this backdrop, we examined patterns in foundation funding and individual donations reported by INN members.

Are there disparities in foundation funding for BIPOC-led versus white-led outlets?

The answer to this question is nuanced and multifaceted: Some BIPOC-led outlets, particularly state and local outlets and startups, report higher levels of foundation funding than white-led counterparts. But the reverse pattern occurs among more established national outlets. The flexibility of funding also varies, with BIPOC-led outlets less likely to receive general operating support from foundations.

At a sector level, the total amount of foundation funding going to white-led outlets far exceeds the total amount going to BIPOC-led outlets (Figure 12). This lopsided distribution matches the much higher number of white-led outlets compared to BIPOC-led outlets in INN’s membership: The amount of funding going to white-led and BIPOC-led outlets is roughly proportional to their respective prevalence in the sector.This pattern suggests that the overall distribution of foundation funding in the sector reflects an equality lens. An equity perspective might prompt us to ask how foundation funding takes into account historical exclusion and oppression that created the racial wealth gap.

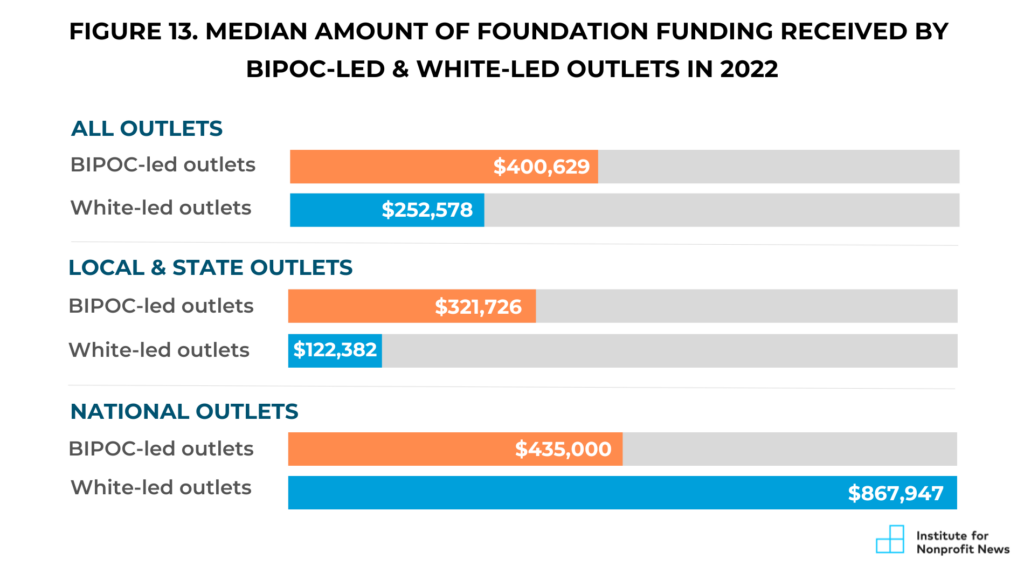

To probe this further, we examined the median amount of funding for BIPOC-led outlets compared to white-led outlets. The median amount of funding reported by BIPOC-led outlets was about 1.6 times higher than the median amount reported by white-led outlets (Figure 13). This pattern stayed the same when we narrowed our focus further, looking at the smaller subset of outlets that are both BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving.28

What might help explain this pattern? Informed by suggestions from INN members and advisory board members, we explored two potential factors that could be driving the overall pattern: geographic scope and launch year (i.e., startups versus more established outlets). We suggest caution in interpreting these patterns, given that some subgroups in our analysis of geographic scope and launch year have only a small number of outlets (n<10), but preliminarily, our analysis suggests that these two factors do matter. Outlets at the state and local level show the biggest funding advantage for BIPOC-led outlets relative to white-led outlets. Meanwhile, among national outlets, the pattern is reversed: White-led outlets reported a higher median amount of foundation funding than BIPOC-led outlets.

Philanthropic support for BIPOC-led startups is an interrelated piece of the puzzle: The median amount of foundation funding among BIPOC-led startups is about 4.5 times the median among white-led startups. (For purposes of this report, INN defines “startups” as outlets established between 2020 and 2022.) The difference is particularly pronounced at the state and local level, where the median amount of foundation funding among BIPOC-led startups is six times higher than among white-led startups. This may partly explain why BIPOC-led outlets at the state and local level report higher foundation funding than white-led outlets.

Meanwhile, philanthropic support for more established BIPOC-led outlets (launched prior to 2020) shows a different pattern. These outlets tend to report lower levels of foundation funding than their BIPOC-led startup counterparts. And among national outlets in particular, they lag behind white-led outlets: The median amount of foundation funding among national white-led organizations launched prior to 2020 was 4.1 times the median among their BIPOC-led counterparts.

When it comes to accessing general operating support from foundations, BIPOC-led outlets report lower levels of this kind of flexible funding compared to white-led outlets. The median BIPOC-led outlet reported that 56% of foundation dollars received in 2022 were available for general operating expenses, compared to 70% among white-led outlets (Figure 14). This suggests BIPOC-led outlets tend to receive more restricted grants than white-led outlets. In our interviews, BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving outlets highlighted funders’ resistance to providing general operating support as a problem that significantly undermines their organizational growth and ability to sustain the work. One said, “We have told funders over and over, if you are only going to fund the really cool idea, that cool idea is going to fizzle out in 2-5 years. Because you have to fund the operations team, the admin team, the CPO. If you really love this cool idea, you have to create a sustainable organization that can keep it going. In the end, what it comes down to are the teams who are actually able to sustain the work — and that takes general operating support.”

It is important to contextualize these findings: They cannot be treated as representative of all BIPOC-led and/or BIPOC-serving news outlets in the U.S. — nor do they capture the full picture of how inequities in philanthropic support have impacted and continue to impact BIPOC-led outlets.

As noted earlier, we do not recommend generalizing these findings to the full universe of BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving outlets in the U.S. — which includes many for-profit outlets serving specific racial, ethnic and language communities, as well as an unknown number of nonprofit outlets that are not INN members.29

Even among INN members, we recognize that the median doesn’t reflect the experiences of all BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving outlets. Some of those we interviewed said the findings did not resonate with their experience accessing foundation funding. Other BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving INN members were less surprised by the findings, based on their observations of recent shifts in philanthropic priorities. This bifurcated response aligns with findings from a 2023 NORC study of nonprofit and for-profit newsrooms, which found that 56% of the organizations that said they primarily focus on serving the information needs of communities of color reported an increase in philanthropic funding in the last five years.30

To the extent that foundation funding has shifted towards BOPIC-led or BIPOC-serving outlets, interviewees emphasized that this is a recent development traced in large part to funders’ increased focus on DEI since 2020. One interviewee commented, “Our organizations have historically not been the recipients of foundation funding. Last year [2022] was an outlier. It was not the norm. The analysis of funding has to look at what happened prior to 2020 to see that it was a major change.” Another noted, “We ended up getting all the grants that we applied for last year. That blew my mind because it was such a stark departure from previous years.”

Interviewees observed that this shift within philanthropy includes changes in longtime journalism funders’ grantmaking priorities and criteria, and the emergence of newer funds focused on supporting BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving news organizations. There are also opportunities for outlets to pursue grants from justice-oriented foundations that don’t have a specific focus on journalism. One interviewee explained, “Looking at funders outside of journalism has been a big success. They don’t have journalism-specific grant opportunities, but they give to justice-oriented work. And they just ‘get’ the work immediately. You don’t have to explain as much.”

To the extent that philanthropic funding has shifted, it needs to be interpreted in relation to historical patterns of inequity and oppression.

Interviewees questioned whether the current focus on DEI — including an increased philanthropic focus on supporting BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving organizations — is proportional to the systemic harm and inequities experienced by people of color across hundreds of years. As one interviewee observed, “I see mainstream groups wanting to start trying to do things differently. But I don't think it's close to enough … just because you hire one person of color in a white foundation, how much harm is caused to that person standing alone, or what can they actually do in those spaces? I think we're a long way from it being sustainable or done in a way that is appropriate for the level of harm that's been allowed here in the States for hundreds of years.”

“Funders need to really think about why they have the hoops that they have in place for creatives and media makers. Is it about control?...Or is it really about making resources available for groups to be at the same level as other groups with inherited wealth or decades of support that weren't offered to communities of color?”

- Interviewee

Even in the current context, some funder practices continue to perpetuate inequities, contradicting the push to advance DEI. Interviewees described recent experiences with racial bias in funders’ decisions about whether, how much, and under what terms they are willing to fund BIPOC-led outlets versus white-led outlets. For example, one interviewee described their outlet’s struggle for “legitimacy” in the eyes of foundations, noting times when they were able to get funding because they asked a white person to speak up for them. Another interviewee observed that some funders’ support for Spanish-language media seems more performative, rather than substantive or equitable: They give out small grants that come with heavy reporting requirements and do not match the amounts awarded to English-language outlets. Another interviewee raised a related issue: The perception among many funders that it is “risky” to invest in a BIPOC-led outlet at the same levels they are willing to invest in a white-led outlet.

More broadly, interviewees flag the need for funders to bring a stronger equity lens to their work supporting BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving outlets. Another interviewee noted, “Funders need to really think about why they have the hoops that they have in place for creatives and media makers. Is it about control? Is it coming from this old lens of philanthropy? Or is it really about making resources available for groups to be at the same level as other groups with inherited wealth or decades of support that weren't offered to communities of color?”

27. Nonprofit Finance Fund, “2022 State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey.” Meredith D. Clark and Tracie M. Powell (2023), “Architects of Necessity: BIPOC News Startups’ critique of Philanthropic Interventions” ISOJ Journal, 13(1), 115-141.

28. We also experimented with tightening our definition of “BIPOC-led” from outlets with majority-BIPOC executives and managers to outlets with majority-BIPOC executives and managers and a majority-BIPOC board. The median amount of foundation funding reported by this smaller group was slightly higher — approximately 2.1 times greater than the median among white-led outlets.

29. To our knowledge, there is no comprehensive directory of all BIPOC-led or BIPOC-serving outlets in the U.S. However, efforts to map BIPOC-serving news media indicate that hundreds of such outlets exist. For example, the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY has identified over 600 Latino news media outlets in its Latino News Media Map and nearly 300 media outlets that primarily serve Black communities in its Black Media Directory, which is a project of the Center for Community Media’s Black Media Initiative. In addition, a directory of ethnic media in California, compiled by Ethnic Media Services, lists nearly 300 outlets for that state alone. By comparison, INN’s 2023 Index included 60 BIPOC-led outlets — 41 of which indicated they were BIPOC-serving.

30. NORC at the University of Chicago, “Journalism and Philanthropy: Growth, Diversity, and Potential Conflicts of Interest” (NORC: 2023).